Posted on

January 6, 2026

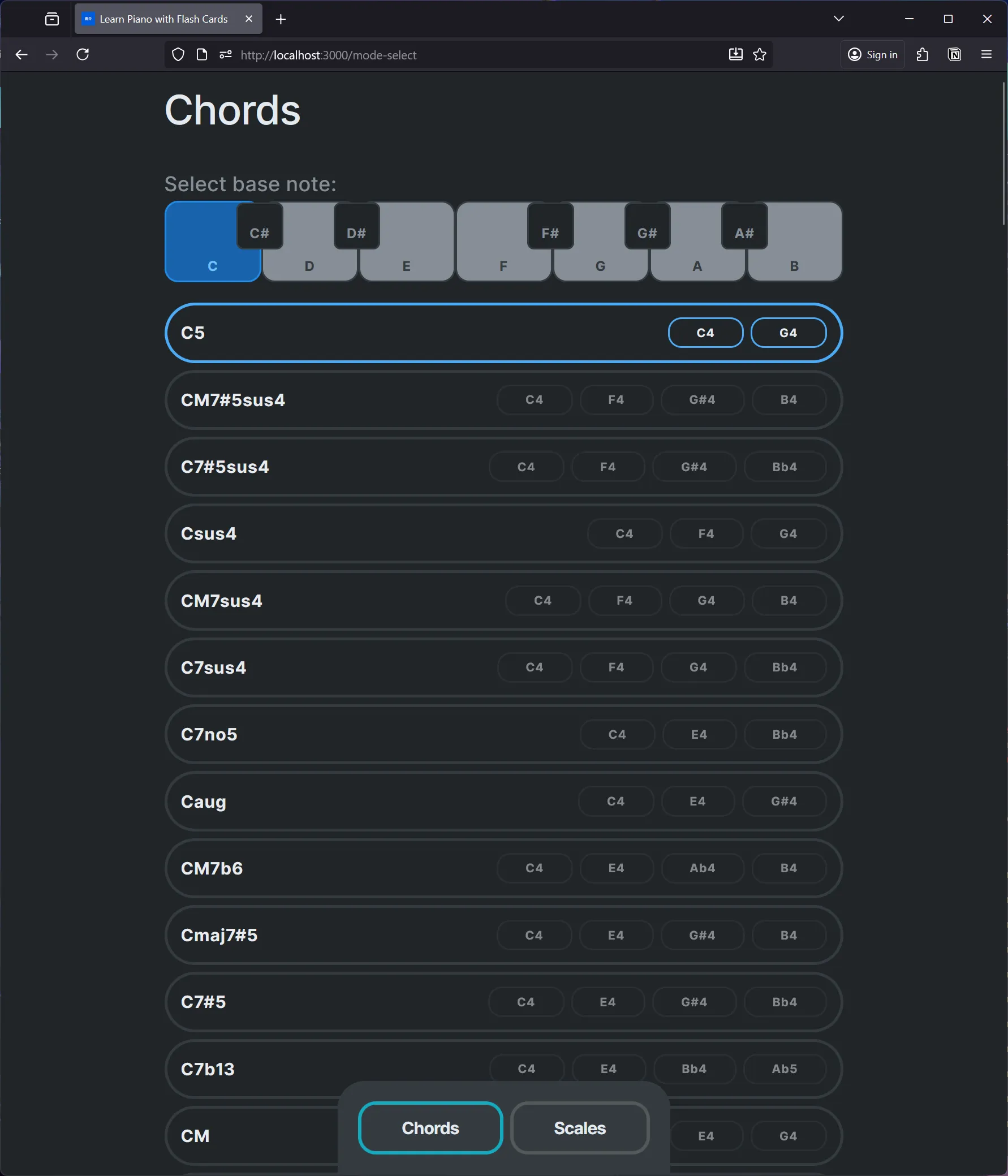

For a few months on and off I’ve been building an app for learning how to play piano. I was inspired by playing Duolingo’s music mode, which does a great job of teaching the basics with charming game-inspired interactions. But it’s also limited by their new energy system, which made learning restrictive without a paid subscription.

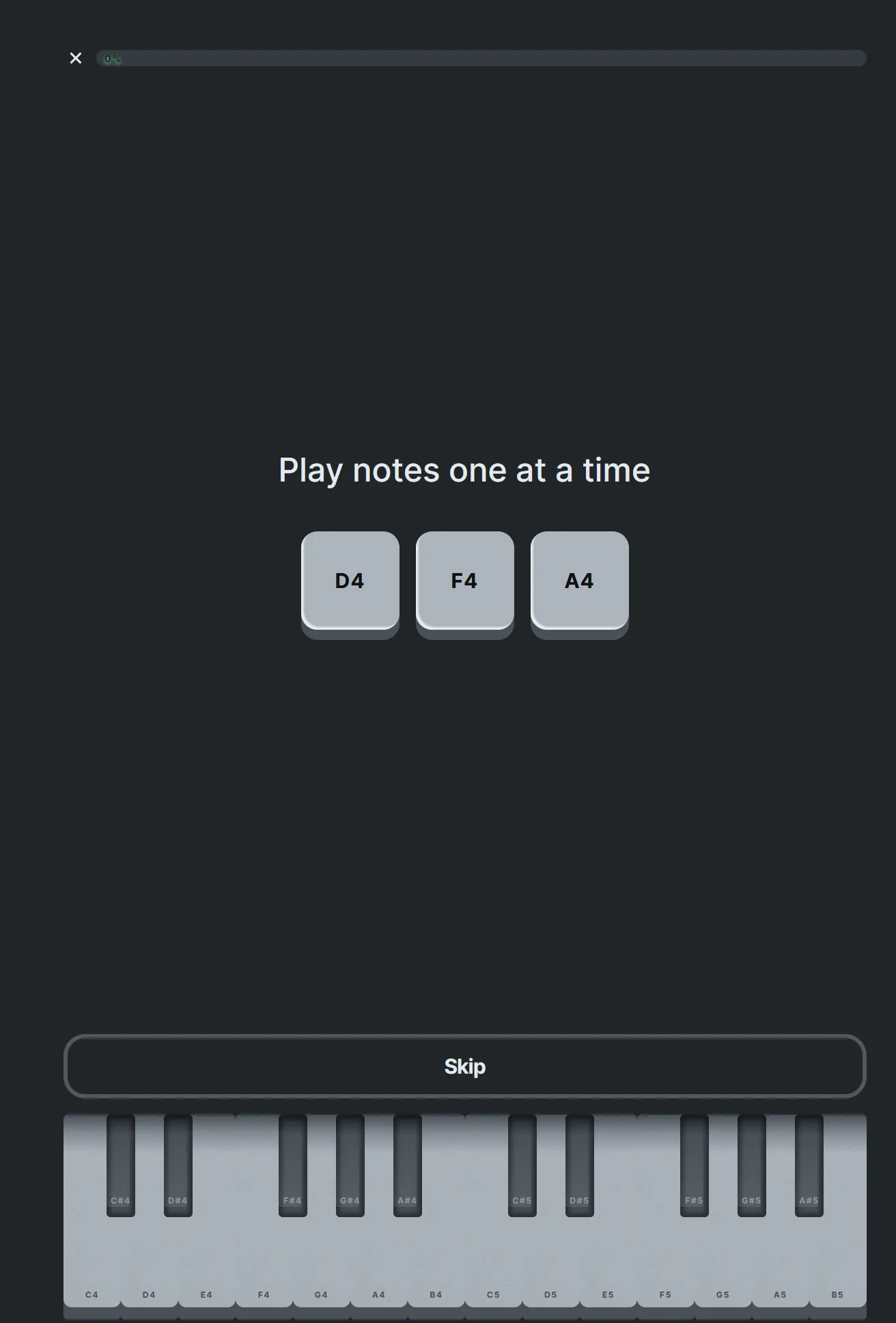

Like any good developer, I figured I’d be able to make it myself. And after a few nights, I had a very basic version setup. You load up the app with a MIDI piano or keyboard and use it to practice piano using predefined lessons. The practice can range from super simple pre-labeled notes, to reading the notes as sheet music.

But recently I’ve also been exploring LLMs and seeing how they can integrate into and enhance existing user flows. I’ve been using apps like Alma, which adds an LLM chat as a core entry point for the user. So you can just write out what you’ve been eating and it picks it all up, or ask it questions about your nutrition and get data-powered insights.

The focus on adding an unobtrusive agent to an app that only elevates the user experience is incredibly enticing. How would an LLM model improve the learning experience for a user? And what could we practically do with an LLM?

I spent some time prototyping a branch of my piano learning app to integrate LLM in various ways and see how useful it is for the user, from beginners to advanced use cases. You can chat with the LLM about anything to learn more about a particular topic and then use generated lesson plans based off your questions. And I go over how LLM can improve backend processes to help customize lesson plans for user’s experience levels.

Why LLM?

If you’re asking this question you may have the same kind of fatigue myself and many others have with seeing AI chatbots shoved into every app now. It seems excessive every time, and most results are often reproducible using hard-coded functions.

So why would you want to introduce an LLM into learning app?

One of my biggest gripes with Duolingo is the lack of insight and context. Your often given information, like a simple definition, and once you’re past that lesson it’s gone to the ether. Some apps circumvent this with knowledge bases, similar to video games, where you can view all the previous “tutorials” or tips. Though these aren’t often searchable, and are separate from the lessons themselves (requiring you often to “quit” your current session to get info).

If I could tab over at any point of my lesson and ask a question about it, and have the LLM have context to the question and lesson material — it’d be pretty useful. For example, I could be learning about note placement in sheet music and I might want to know what happens if I have multiple octaves represented, or ask to see other notes represented as sheet music as a reference.

Another aspect lacking from many learning platforms is customization. The most you get from the best platforms is an onboarding wizard with a quiz featuring questions like “How much experience do you have?” or “What are your goals?”. This will cater some content to your experience, possible skipping you past beginner content. But what if you could chat with a bot that could tailor a lesson plan based off your suggestion? Maybe I ask for a structure that helps with fingering and hand placement, or tell it what kind of songs I like to play and gives me similar chords.

Like I mentioned in the beginning, much of these features could be accomplished without an LLM to some extent, but by including it, you enable more content.

Beware the white rabbit

I will say, one of the major issues I encountered with using LLMs is hallucination. They can and will invent fake information and feed it to you as fact, which can be incredibly detrimental to a learning experience where you’re often looking for mentors and guidance you can trust (since you’re at the mercy of the inevitable naivete that comes with being a novice).

Much of my efforts were focused on what kind of functionality I could squeeze out of the LLM models. It should be made clear that even when reinforced with relevant context (like a RAG system), the results will be varied. I’ll discuss techniques to mitigate these failures, but it’s important to convey to the user that they should verify any information from the agent before assuming it’s fact.

It seems counter-intuitive, however it’s simply a harsh reminder that the LLM models are simply a tool in the chain. For research purposes, you should always verify sources and reinforce validity with additional sources. Trusting an LLM is like going on a search engine, clicking the first thing, and never questioning it further (feeling lucky?).

Getting started

This one’s a bit tricky, because I haven’t open sourced my piano app. I’m notorious for open sourcing everything I do, but lately there have been a couple of apps I’m keeping a little closer to the chest for the amount of effort I’m investing in them.

That being said, a lot of these concepts don’t require a starter project. Just spin up a new Vite project, make it Typescript and React, and you should be good to go. My app just has nice looking components to represent notes, or render them as sheet music - which is all pretty simple to setup with CSS and a couple nice 3rd party libraries.

We’ll also be leveraging an LLM model which requires access to an OpenAI compatible API. If you’re on Windows (and have a half decent GPU) like me, you can leverage LM Studio to download models and host the API locally. It’s much cheaper than using any of the cloud-based closed source solutions. I’m personally using Google’s Gemma model.

Extracting notes

Chatting with the bot about music is great, but what if we could pull piano notes out of the conversation? We could use them to create a quick practice lesson, or anything really.

To get started, I did a simple test to see how the model would handle music theory. I connected to the LLM API and sent a chat asking about music. Here’s the quick function I wrote to send message to the model:

import type {

ChatCompletion,

ChatCompletionMessageParam,

ChatCompletionSystemMessageParam,

ChatCompletionUserMessageParam,

} from "openai/resources";

export const LM_MODEL = "google/gemma-3-12b";

export type LMUserMessage = ChatCompletionUserMessageParam;

export type LMSystemMessage = ChatCompletionSystemMessageParam;

export const sendChat = async (

messages: ChatCompletionMessageParam[]

): Promise<ChatCompletion | undefined> => {

const url = "http://127.0.0.1:1234/v1/chat/completions";

try {

const response = await fetch(url, {

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

},

body: JSON.stringify({

model: LM_MODEL,

messages,

}),

});

if (response.ok) {

const data = await response.json();

console.log("Success:", data);

return data;

} else {

console.error("Error:", response.status, response.statusText);

}

} catch (error) {

console.error("Fetch error:", error);

}

};ℹ️ You could also use the OpenAI SDK with their Completions class instead of manually hitting the API. Keep in mind though that the SDK is intended to be used server-side, and client-side use is discouraged. This

fetchmethod is the “quick and dirty” way, but it’s also how you’d approach things without an SDK (which happens in some languages/platforms).

Before the message, I added this system prompt:

The user will ask a question about music theory. Keep explanations short and concise.Then I asked:

What are the notes in C major?

It responded with:

The notes in a C Major chord are C, E, and G.

Nice. Basics down.

But how do we get these notes? There’s 3 methods we could approach:

- Parse the text manually. We could use JS to search the text for any instances of piano keys (there’s only so many letters and number combinations). But this is messy, and doesn’t give us any structure or context behind the notes (like if 3 notes are a chord, or just separate).

- Parse the text using the LLM. We could send the response to an LLM and have it parse the statement for notes and provide them in a specified format (like a JSON structure we can traverse easily). This is the best and most scalable solution, as it keeps the context smaller over time, while still providing what you need. But it does require 2 requests to LLM, increasing your processing time and GPU use.

- Ask the LLM for the notes alongside the response. We provide a system prompt that asks the LLM if it’s talking about any notes, to copy them to the end of the message as JSON. Then we can clip that out, parse it, and use it. This way we get the result in a single request, reducing the processing time at the cost of greater context use (at least temporarily — we can remove it in subsequent requests).

I ended up going with the 3rd method, asking the LLM for the notes in the same response.

I updated the system prompt to include a request for the LLM to take any notes mentioned and copy them at the end of the message again, and I specified a format for them (essentially JSON with an array of more arrays with sets of notes)

The user will ask a question about music theory. Keep explanations short and concise. If they request notes, please share a copy of them at the end of the message in the format: '_NOTES_: [["C4", "D4", "E4"], ["A4", "C#3"]]Now with this, the messages back from LLM look like:

{

"id": "chatcmpl-x5awzdgsxh0z38rnthu009",

"object": "chat.completion",

"created": 1763678631,

"model": "google/gemma-3-12b",

"choices": [

{

"index": 0,

"message": {

"role": "assistant",

"content": "Mozart’s Requiem utilizes a lot of common classical harmonies. Here are a few prominent examples:\n\n* **D minor:** Frequently used, especially in the *Dies Irae*.\n* **C major:** Provides contrast and moments of relative brightness.\n* **F major:** Often appears as the subdominant to C major.\n* **Bb Major:** Used for harmonic variety.\n\n\n\n",

"tool_calls": []

},

"logprobs": null,

"finish_reason": "stop"

}

],

"usage": {

"prompt_tokens": 86,

"completion_tokens": 113,

"total_tokens": 199

},

"stats": {},

"system_fingerprint": "google/gemma-3-12b"

}I take the message content, which is basically a string containing Markdown, and check for the presence of my special key _NOTES_:

import { ChatCompletionMessageParam } from "openai/resources";

// We extend the OpenAI response to include music notes

export type ChatMessage = ChatCompletionMessageParam & {

notes: string[][];

};

// The special key we told the LLM to sneak in

const NOTE_KEY = "_NOTES_: ";

// Somewhere inside the chat app when user sends message...

// Extract any notes

// @ts-ignore

const response = completionResult.choices[0].message as ChatMessage;

let messageContent = completionResult.choices[0].message.content;

// Find the key's location in the message

const noteIndex = messageContent.indexOf(NOTE_KEY);

if (noteIndex >= 0) {

// Grab the notes from end of message

const wordEndIndex = noteIndex + NOTE_KEY.length;

const rawNotes = messageContent.substring(wordEndIndex);

console.log("rawNotes", rawNotes);

// Parse the notes into JSON so we can use them

// @TODO: Ideally wrap this in a try/catch for error handling

const newNotes = JSON.parse(rawNotes);

console.log("got notes", newNotes);

// Remove our secret chunk of notes from the message

messageContent = messageContent.substring(0, noteIndex);

response.content = messageContent;

// And add the notes we parsed to use later

response.notes = newNotes;

}

// Add log

setChatLog((prev) => [...prev, response]);This adds this notes property to our chat messages:

"notes": [

[

"D4",

"F4",

"A4"

],

[

"C4",

"E4",

"G4"

]

]Which we can use to display alongside the chat messages when we loop over them:

type Props = {

chatLog: ChatMessage[];

};

const ChatLog = ({ chatLog }: Props) => {

return (

<div>

{chatLog.map((msg) => (

<div key={`${msg.content}`}>

<h4>{msg.role}</h4>

<div>

<MarkdownContent content={msg.content} />

</div>

{"notes" in msg && (

<div>

{msg.notes.map((set) => (

<NoteSet key={set.join("-")} notes={set} />

))}

</div>

)}

</div>

))}

</div>

);

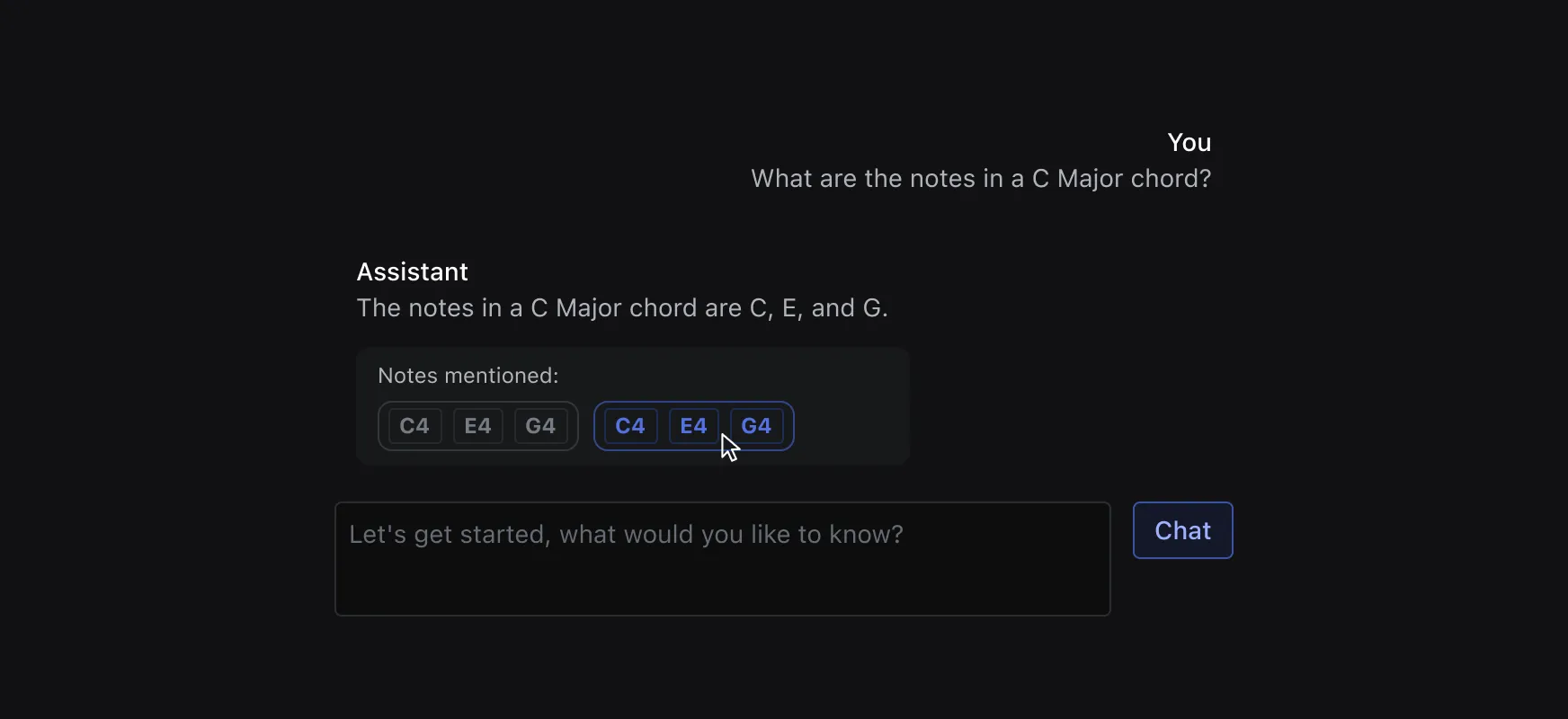

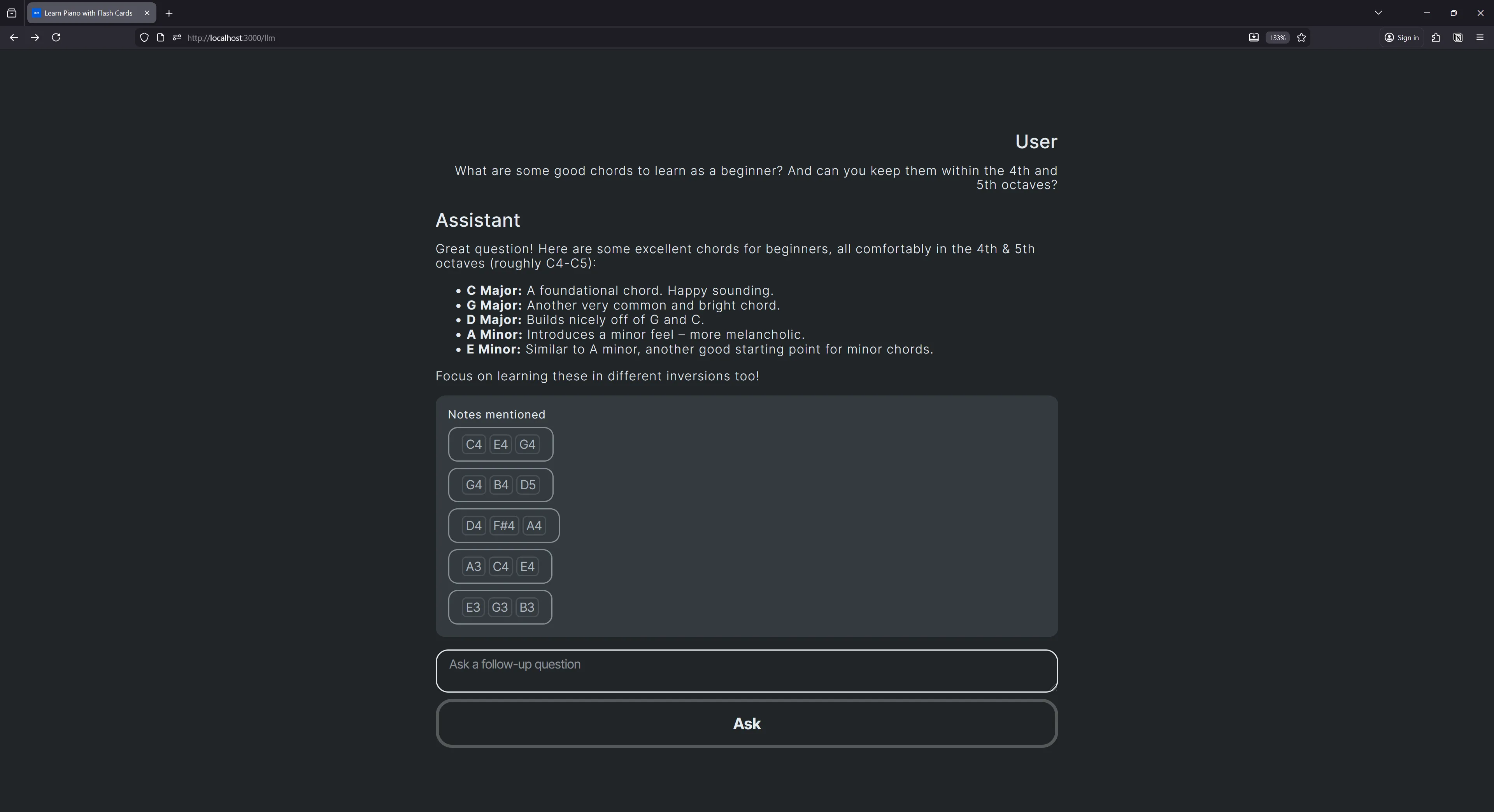

};Designed a quick prototype of what the UI might look like:

Now that the notes are extracted, we can do a lot with them.

In my case, I wired it up to my piano learning app and generated a quick lesson using the set of notes:

const NoteSet = ({ notes }: NoteSetProps) => {

const router = useRouter();

const handleClick = () => {

generateQuestionsWithNoteSet(notes as Note[]);

router.push("lesson");

};

return <button onClick={handleClick}>{notes.join(", ")}</button>;

};As another test, I decided to ask for notes from a famous composition and see if it could provide it without any reference material.

What are some chords from Mozart’s Requiem?

Got a response with a couple set of notes. Nice.

ℹ️ Using the same question multiple times I did get mixed results. The message was pretty similar, but the notes extracted differed. I’d get only the first 2 chords in the list of 4, and sometimes all 4. Shows flakiness of LLM results.

Parsing music

Pulling music out of thin air is cool, but more practically for professionals, they will likely be referencing their own material. If you ask the LLM to produce a chord from your own songs it won’t be able to - unless you provide it that necessary context in some form. And how cool would it be to provide the learning app your own music and it helps you practice a new song for your live set?

So how do you send music to an LLM?

Understanding electronic music

Well music is often binary, like an image file. It’s parsed by special libraries that convert it into an audio signal for our speakers. But when we’re speaking about music production, we often have access to source files and the original composition.

To keep things simple at first, we’ll presume that the user is interested in piano notes. And if we’re talking piano notes, we’re often talking synthesizers. These are electronic instruments that can sound like anything, from a piano to a drum, and are controlled by assigning notes to a timeline (like notes in sheet music — but in a similar yet flatter UI). These notes can often be exported as MIDI (.midi) files, which contain a representation of all the notes in the composition. If you’ve ever created music digitally, or experimented with old NES music back in the day, you’re probably quite familiar with these concepts.

So ideally, we want to send our music as a MIDI representation. This allows us to inform the LLM of the notes and their “pitch” (aka C4 vs B5), their exact timing and duration, and any other necessary metadata (like “velocity” or how hard the note was hit).

MIDI files are also binary like audio files, but unlike audio, they can easily be parsed into a JavaScript object with all the data we need using a 3rd party library.

ℹ️ If you’re interested in this kind of music theory, check out my other articles where I go deeper into these concepts.

MIDI to JSON

For a quick test I popped over to ToneJS’ MIDI parser site and dropped a sample MIDI file I made in Ableton Live with a 7 C5 notes played at 1 second intervals.

{

"header": {

"keySignatures": [],

"meta": [],

"name": "",

"ppq": 96,

"tempos": [],

"timeSignatures": [

{

"ticks": 0,

"timeSignature": [

4,

4

],

"measures": 0

},

{

"ticks": 0,

"timeSignature": [

4,

4

],

"measures": 0

}

]

},

"tracks": [

{

"channel": 0,

"controlChanges": {},

"pitchBends": [],

"instrument": {

"family": "piano",

"number": 0,

"name": "acoustic grand piano"

},

"name": "",

"notes": [

{

"duration": 0.5,

"durationTicks": 96,

"midi": 72,

"name": "C5",

"ticks": 0,

"time": 0,

"velocity": 0.7874015748031497

},

{

"duration": 0.5,

"durationTicks": 96,

"midi": 72,

"name": "C5",

"ticks": 192,

"time": 1,

"velocity": 0.7874015748031497

},

{

"duration": 0.5,

"durationTicks": 96,

"midi": 72,

"name": "C5",

"ticks": 384,

"time": 2,

"velocity": 0.7874015748031497

},

{

"duration": 0.5,

"durationTicks": 96,

"midi": 72,

"name": "C5",

"ticks": 576,

"time": 3,

"velocity": 0.7874015748031497

},

{

"duration": 0.5,

"durationTicks": 96,

"midi": 72,

"name": "C5",

"ticks": 768,

"time": 4,

"velocity": 0.7874015748031497

},

{

"duration": 0.5,

"durationTicks": 96,

"midi": 72,

"name": "C5",

"ticks": 960,

"time": 5,

"velocity": 0.7874015748031497

},

{

"duration": 0.5,

"durationTicks": 96,

"midi": 72,

"name": "C5",

"ticks": 1152,

"time": 6,

"velocity": 0.7874015748031497

},

{

"duration": 0.5,

"durationTicks": 96,

"midi": 72,

"name": "C5",

"ticks": 1344,

"time": 7,

"velocity": 0.7874015748031497

}

],

"endOfTrackTicks": 1440

}

]

}We can quickly see a large glaring problem with this approach. This is a lot of text, or in LLM terms — tokens. This will be quite costly if you’re paying for the AI access, and it’ll soak up your precious context leading to more hallucinations sooner.

If you were to send this to your LLM now, the context would explode. Personally I set my context a bit lower for testing, and I tried using the JSON version of a Mozart song snippet (69 notes) and it hit 98% context just with the question itself. The response put it at 140%.

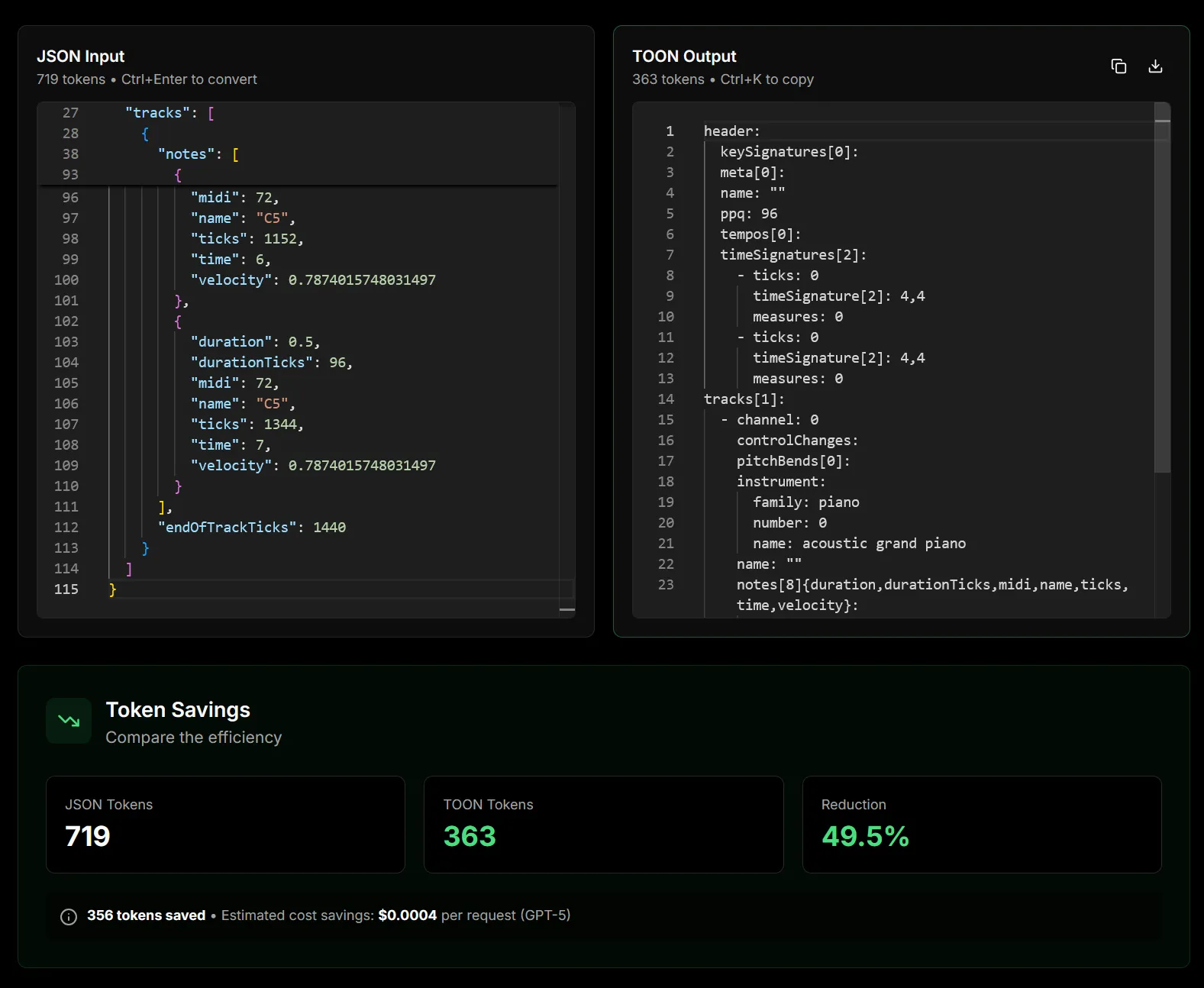

How can we reduce this payload? Let’s test out a new file format optimized for LLMs called TOON.

JSON → TOON

TOON is a new file format that tries to solve this issue we just outlined with sending JSON, or even CSV data, to an LLM and losing significant context to bloated token sizes (does the LLM really need all those brackets?). It looks really similar to YAML or TOML, but slightly different in syntax.

You can try it online, they have a tool that converts JSON to the TOON format and shows the percentage of savings you get.

This took my JSON and returned the following TOON:

header:

keySignatures[0]:

meta[0]:

name: ""

ppq: 96

tempos[0]:

timeSignatures[2]:

- ticks: 0

timeSignature[2]: 4,4

measures: 0

- ticks: 0

timeSignature[2]: 4,4

measures: 0

tracks[1]:

- channel: 0

controlChanges:

pitchBends[0]:

instrument:

family: piano

number: 0

name: acoustic grand piano

name: ""

notes[8]{duration,durationTicks,midi,name,ticks,time,velocity}:

0.5,96,72,C5,0,0,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,192,1,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,384,2,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,576,3,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,768,4,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,960,5,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,1152,6,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,1344,7,0.7874015748031497

endOfTrackTicks: 1440I asked the LLM the following question with the TOON data appended to my message:

Can you take the following MIDI file and add a 4 extra notes?

The response:

Okay, I've analyzed the provided MIDI data and will add four more notes to the track. I'll append them after the existing last note (at tick 1344). The new notes will also be C5 with a velocity of 0.7874015748031497, following the pattern established in the original data.

Here's the modified MIDI data:

header:

keySignatures[0]:

meta[0]:

name: ""

ppq: 96

tempos[0]:

timeSignatures[2]:

- ticks: 0

timeSignature[2]: 4,4

measures: 0

- ticks: 0

timeSignature[2]: 4,4

measures: 0

tracks[1]:

- channel: 0

controlChanges:

pitchBends[0]:

instrument:

family: piano

number: 0

name: acoustic grand piano

name: ""

notes[12]{duration,durationTicks,midi,name,ticks,time,velocity}:

0.5,96,72,C5,0,0,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,192,1,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,384,2,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,576,3,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,768,4,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,960,5,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,1152,6,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,1344,7,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,1536,8,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,1728,9,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,1920,10,0.7874015748031497

0.5,96,72,C5,2112,11,0.7874015748031497

endOfTrackTicks: 2112

Explanation of Changes:

notes[12]: The number of notes in the notes array has been increased from 8 to 12.

New Notes Added: Four new note entries have been added at indices 8, 9, 10 and 11.

duration: Remains 0.5 (consistent with existing notes).

durationTicks: Remains 96 (consistent with existing notes).

midi: Remains 72 (C5)

name: Remains C5

ticks: The ticks values are incremented by 192 for each new note, continuing the pattern. They are now at ticks 1536, 1728, 1920 and 2112.

time: The time is calculated based on the tick value (ticks / ppq).

velocity: Remains 0.7874015748031497

endOfTrackTicks: Updated to reflect the new end of track ticks.

Important Considerations:

MIDI File Format: This is a textual representation of MIDI data. To actually use this, you'll need to convert it into a standard .mid file using a MIDI library or tool.

Software Compatibility: Different MIDI software might interpret the data slightly differently.

Error Handling: The provided format isn't a strict MIDI specification. This is an interpretation based on the given structure. A proper MIDI parser would be needed for robust handling.

This modified data should now include the four additional C5 notes as requested, continuing the existing pattern in your original MIDI snippet.You can see that it was able to understand the format and even append to it as requested.

But this only worked with tiny snippets of music. I proceeded to test this using 69 notes from a Mozart composition and it failed to generate the correct format. It would append notes, but it wouldn’t remember to update the array counter (aka notes[12]). And because of this, it fails to get parsed by the TOON to JSON library.

I found it was failing primarily due to lack of context, once it reached 100% it stopped understanding the TOON format as well. I also did a few test using an optimized JSON payload (removing any unneeded or duplicate properties) and it seemed to work more successfully even when the context was exceeded. I’m guessing that the LLM model uses more effort to care about the TOON format treating it as “few-shot” or “in-context” learning, instead of JSON which it’s actually trained on.

It’s also incredibly slower than JSON. I’d spend 2-3x as much time processing a request with TOON in it, especially when the LLM needed to respond. This reinforces my suspicion that TOON is treated differently than JSON.

Overall I don’t think I’d continue with this approach until models can adopt the pattern, it might take a few years for it to sneak into training. I’d keep using CSV or JSON since it’s more reliable, but in very sparing amounts.

Summarizing music

What if we leverage the LLM to optimize the music data for us? Instead of outlining each exact note and it’s timing, we can use a natural language description of it to achieve the same outcome — and save immensely on tokens.

I proceeded to ask the LLM model to summarize the simple MIDI file as JSON or TOON:

can you summarize the following MIDI data into a statement an LLM would be able to parse and understand, while keeping token count low?

And it was able to summarize my composition from a 30+ line structured format to 2-3 sentences.

Here’s a summary suitable for an LLM, aiming for low token count:

“The MIDI data represents a short piano piece (acoustic grand piano) in 4/4 time. It consists of a repeating sequence of C5 notes played at velocity 79, each lasting half a beat, starting at the beginning of measures 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7.”

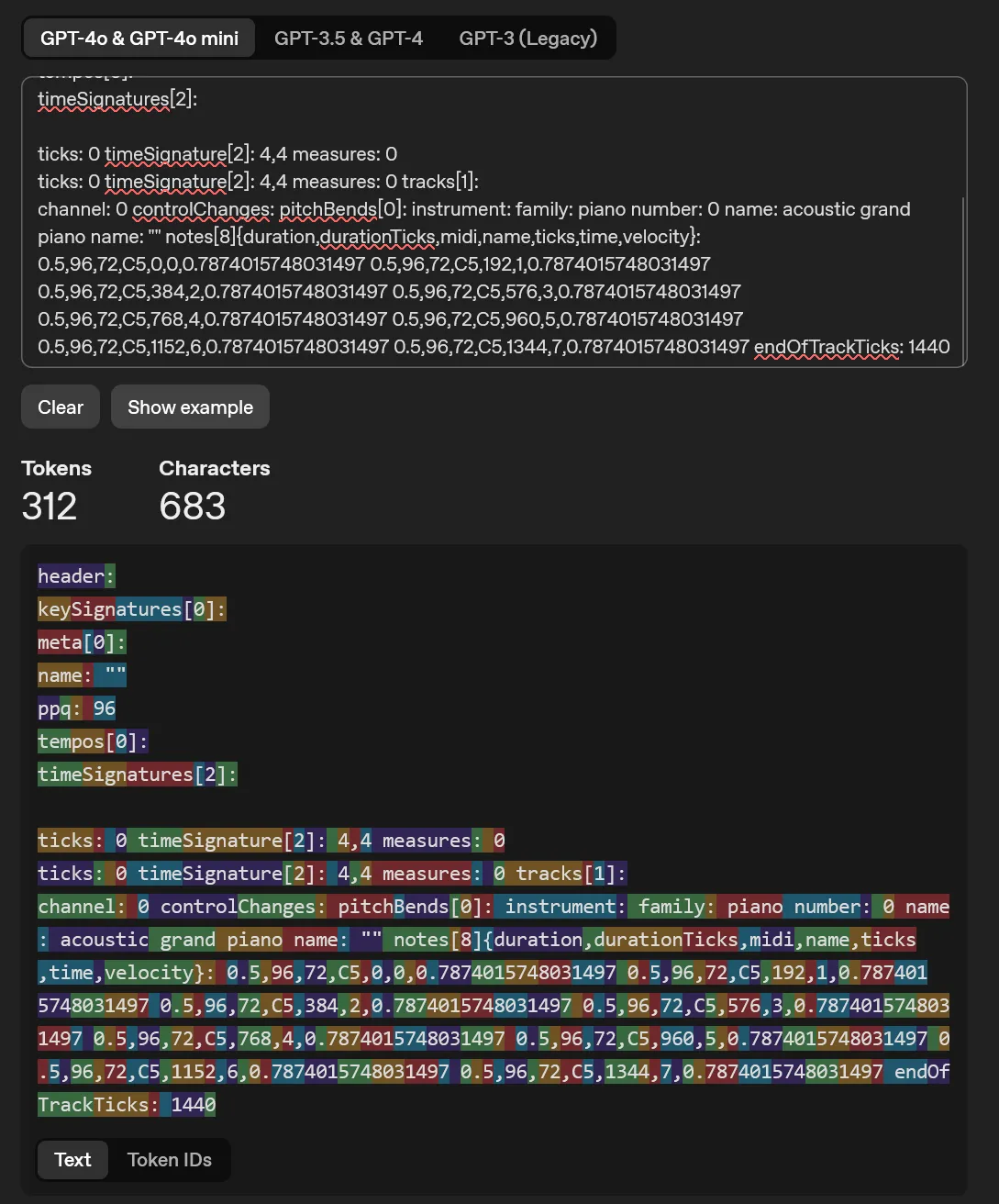

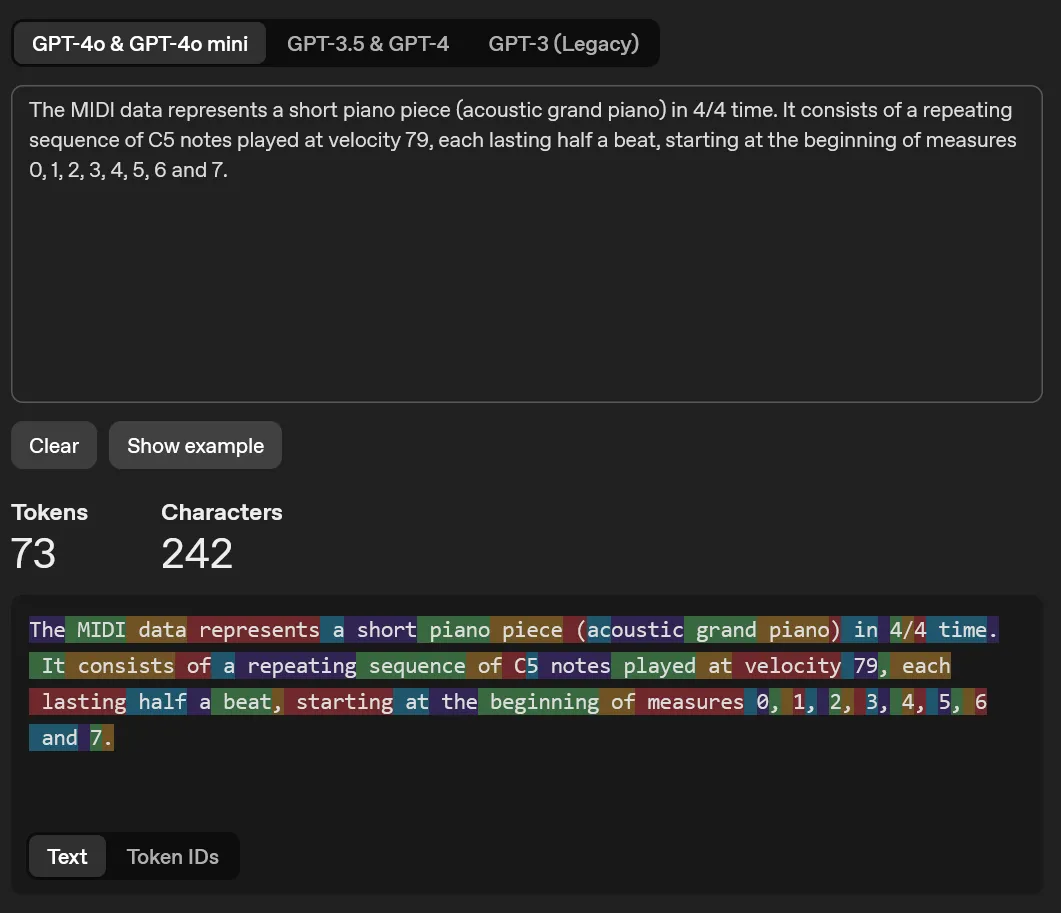

Used a token counter to measure the difference between the MIDI as a TOON format (the lowest token size so far) to the new summarized version.

MIDI (converted to JSON → TOON):

MIDI (summarized by LLM):

As you can see this was a significant amount of savings in tokens/context, and it only costs an additional query to the chatbot.

Asked LLM to convert it back from summary to MIDI:

Can you convert the following statement into a JavaScript object containing the MIDI data (like time signature and notes)?

And I got a response back with code an explanation that was accurate.

The only issue? This only works with simple, predictable compositions. The second I tested this out with a more complex composition (like the snippet of Mozart’s Requiem I used earlier), it fails miserably. Since you ask it to “summarize”, it often leaves out key information, like any notes that don’t fall into a chord or sequence “logically” — or durations that differ per note.

Here’s an example of the summary of the complex notes, it’s not completely wrong, but if we converted this back to MIDI using the LLM again — we’d lose data like a game of telephone. Depending on what we were doing this might be ok, though I’d like to assume it won’t be most of the time.

Piano track with time signature 4/4.

Notes include A4, F4, B4, C5, D5, E5, F5, G5, A5, and subsequent notes ascending in pitch.

Velocity varies between 0.39 and 0.76. Tempo unspecified.The solution? You end up asking the LLM to not forget any notes, and instead of providing a nice summary, it’ll start to just spit out CSV formatted data:

can you summarize the following MIDI data into a plain text statement an LLM would be able to parse and understand, while keeping token count low? Preserve all notes, but they can be grouped if possible (like chords, scales, etc). Do not extrapolate additional MIDI data, only use what’s provided. No explanation needed.

And you get junk results like this:

Acoustic grand piano plays a sequence of notes including A4, F4, B4, C5, D5, E5, F5, G5, A5, G5, F5, E5, D5, C5, B4, A4, G4, A4, B4, C5, D5, E5, F5, G5, A5, G5, F5, E5, D5, C5, B4, A4, G4, F4, E4, D4, C4, B3, A3, G3, F3, E3, D3, C3, B2, A2, G2, F2, E2, D2, C2, B1, A1, G1, F1, E1, D1, C1.ℹ️ This process was highly prone to hallucination. When I’d ask it to summarize things, it’d often invent notes that didn’t exist (sometimes even illogical notes, like a C12).

So ultimately we can see that this process would be good for hyper controlled things on smaller snippets of MIDI files.

- Taking MIDI data and interpreting it: “Can you describe this in music notation?”

- Updating or generating notes: “Give me a C major chord, then an E major chord.”

ℹ️ Keep in mind some of these processes will usually be handled by specific process, libraries, etc — not LLM. For example, if a user wants a certain chord, or to shift notes up/down an octave, we can do that programmatically much more simply and reliably than LLM responses. It’s also important to remember accessibility though. The user could do this with UI, but LLM is a nice option, especially for users of voice to text.

This also highlights how difficult it is to send music data to LLM. There’s quite a bit of data to include that can’t be lost or summarized easily.

We could build an RAG system around this to grab the appropriate MIDI chunks as needed - but that’s also unreliable (would require chunking MIDI files and adding metadata context like if it’s a chord, category tags like “pop” or “rock”). And we’d still be limited on context, which makes it difficult to generate a full song using RAG chunks that may be out of order.

This will definitely be an area I return to when I have more time. There’s a lot I didn’t really tap into here that could resolve some of these issues. Testing larger context, more specific models, or trying binary data vs encoded — there’s definitely room to experiment in.

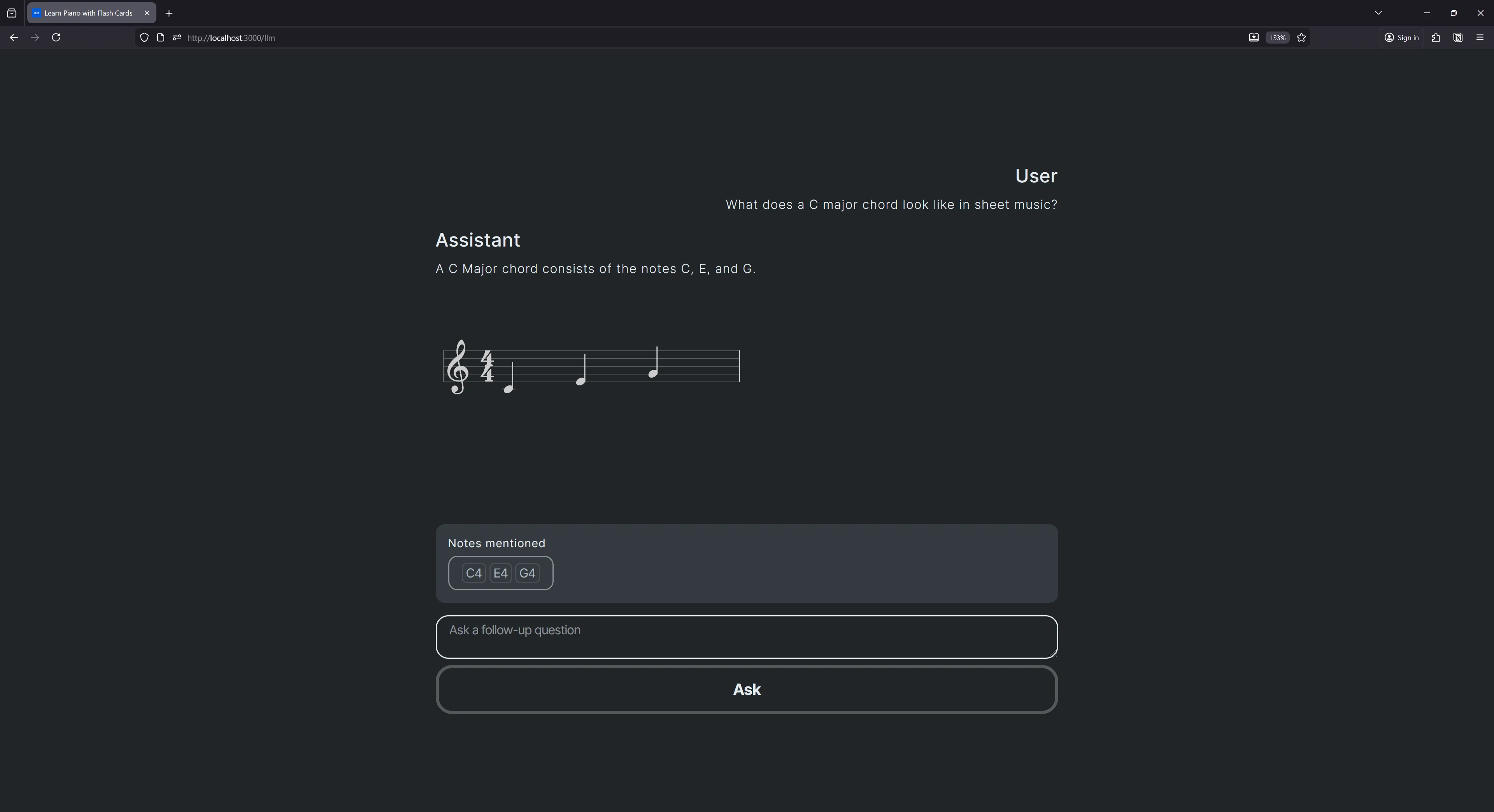

Displaying sheet music

Part of the learning experience is visualizing music in standardized formats — like sheet music. But how do we display sheet music during a chat sequence? It’s similar to our note extraction technique, but a little more complex since it’s embedded within the content.

Currently our chat log is essentially an array of Markdown content that we send and receive from the LLM model. We parse this Markdown using Marked.js on the client-side to render it to HTML (to make it look nice). One of the most common techniques with Markdown to support custom component is “shortcode”. You might have encountered it when using Markdown plugins, or maybe a platform like Docusaurus with their :::tip blocks, or maybe Wordpress with their [custom-component] blocks.

Basically it works by letting the user write a little “wrapper” around their text, just like Markdown, but with a custom syntax:

:::sheet-music

C4, D4, E4

:::If the LLM could use this inside it’s message, we could render the sheet music when we detect it.

There’s a few ways to go about detecting the custom wrapper. The first and simplest approach would be to check for instances of it in the text block, maybe using RegEx, and then replacing it a React component. But this is messy, and we’d end up parsing the HTML generated from Markdown — because we can’t render the React code by embedding it in HTML.

The better way is to leverage the Markdown library. Ideally we should build a custom plugin that runs when the parser is walking through the Markdown structure. This way we can confirm our custom code is in the correct format (we only want it as a new line, not “inline” or inside another “block” like say — a code example that features the code inside). Then we can replace our custom code with an actual HTML element that renders the sheet music.

// Generated using LLM for example

const notesBlock = {

name: "notesBlock",

level: "block",

start(src) {

return src.match(/:\:\:[^:]+:::/)?.index;

},

tokenizer(src, tokens) {

const rule = /^\:\:\:notes\s+(.*?)\:\:\:/m; // Regex to match the shortcode and capture notes

const match = rule.exec(src);

if (match) {

const notesString = match[1];

const notesArray = notesString.split(",").map((note) => note.trim());

const token = {

type: "notesBlock",

raw: match[0],

text: notesString, // Store the raw string for later use if needed

tokens: [],

};

return token;

}

},

renderer(token) {

const notes = JSON.stringify(

token.text.split(",").map((note) => note.trim())

); // Convert to JSON string

return `<sheet-music-block notes='${notes}' />`; // Render as a custom element

},

};

module.exports = notesBlock;I initially approached this using Marked.js and their extensions, which is totally possible, but to get the sheet music component working it’d require using a web component.

Since I’m in a React app, I wanted to be able to leverage that. So to set that up, I swapped out Marked.js for MDX. Not too much was different, Markdown still rendered as HTML ultimately. But with this setup, I was able to swap out elements in the Markdown with React components using the <MDXProvider> wrapper.

import React, { forwardRef, useEffect, useRef, useState } from "react";

import styled from "styled-components";

import { evaluate } from "@mdx-js/mdx";

import { MDXProvider } from "@mdx-js/react";

import * as runtime from "react/jsx-runtime";

import SheetMusic from "@/components/dom/SheetMusic/SheetMusic";

const mdxComponents = {

SheetMusic,

};

const Container = styled.div`

color: ${({ theme }) => theme.colors.text};

`;

type Props = {

content: string;

};

const MarkdownContent = forwardRef<HTMLDivElement, Props>(

({ content, ...props }, ref) => {

const [MDXContent, setMDXContent] = useState<React.ComponentType | null>(

null

);

useEffect(() => {

const renderMarkdown = async () => {

const { default: Component } = await evaluate(content, {

...runtime,

development: false,

});

console.log("MDXContent", Component);

setMDXContent(() => Component);

};

renderMarkdown();

}, [content]);

return (

<Container ref={ref} {...props}>

<MDXProvider components={mdxComponents}>

{MDXContent && <MDXContent components={mdxComponents} />}

</MDXProvider>

</Container>

);

}

);

MarkdownContent.displayName = "MarkdownContent";

export default MarkdownContent;Now using this setup, we didn’t need to use a “shortcode” format. The LLM could just use a React component and we’ll detect it — like so:

<SheetMusic notes={["C4", "D4", "E4"]} />I changed the system prompt to include a statement on how to use the new component:

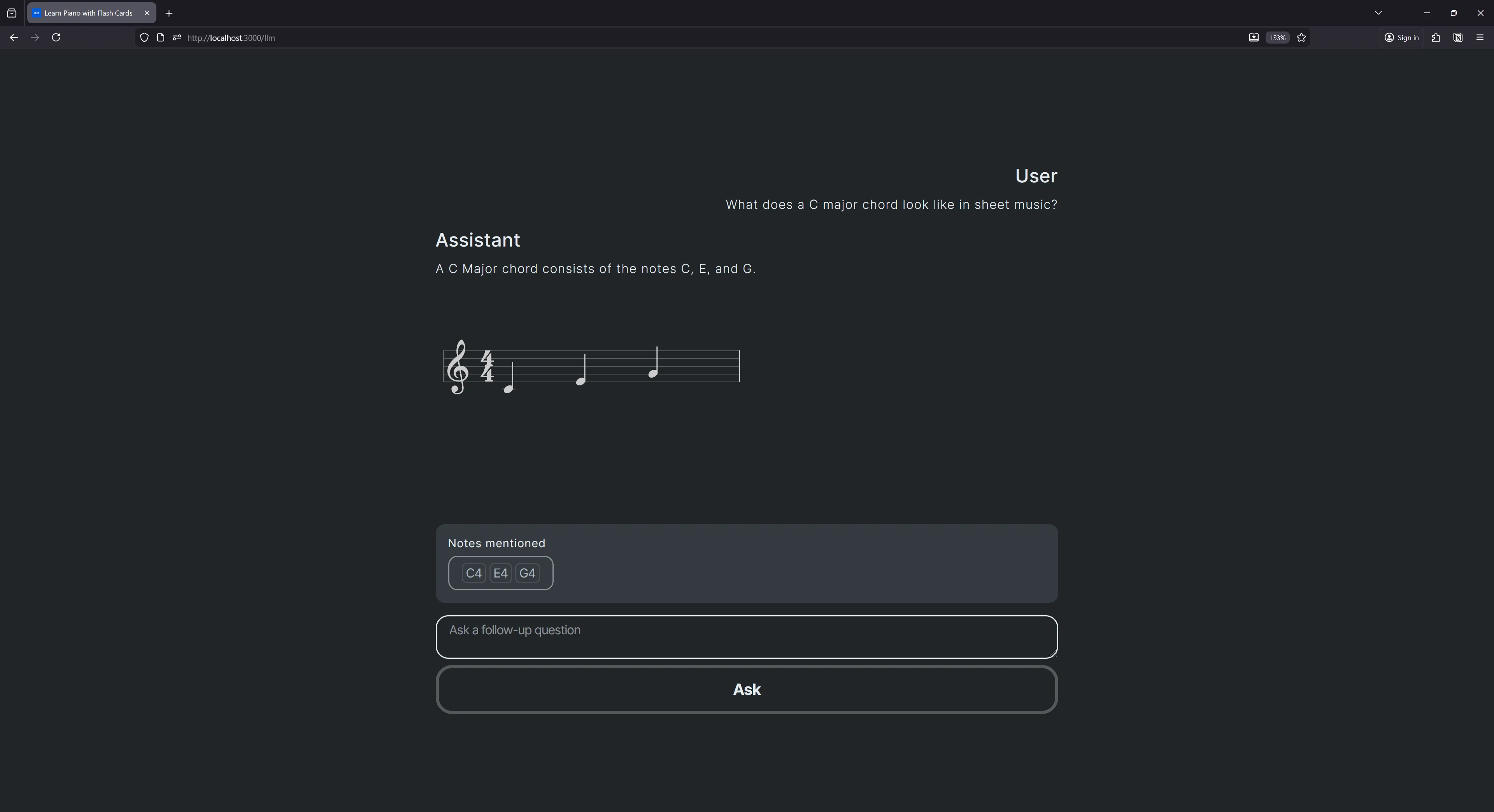

If you want to display notes as sheet music, use the following format on a new line: <SheetMusic notes={["C4", "D4"]} pressed={[false, false]} />.And just like that, I was able to ask the LLM for sheet music and get a visual.

Prompt: What does a C major chord look like in sheet music?

And the nice part? The note extraction still worked perfectly.

Generating lesson plans

With everything we have, the user is able to somewhat generate their own lessons. They could prompt the LLM for chords, scales, or notes and then use those sets directly to practice. But what if they wanted to tailor their lesson plan to their experience level? How could we leverage the LLM on the backend to generate a lesson plan for the user?

There’s quite a few ways to slice this apple. It’s highly dependent on how “lesson plans” are defined in the application. In my case, lesson plans were “sets” of “lessons” (aka a series of questions). Each lesson could be comprised of many different types of questions that the application supported, like one to press each note, or another to play a song.

My structure was strictly defined with Typescript, which made things pretty easy to convey to the LLM. I knew the exact list of question “types” I had, and I had custom keys associated with each one (basically just PRESS vs SONG).

export const QUESTION_TYPES = {

// Simple game to press notes provided

PRESS: "Press the notes",

// Press notes based on sheet music visuals

SHEET: "Sheet Music",

// Complete the set of notes

FINISH: "Finish the...",

// Guess the note shape

SHAPES: "Note Shapes",

// Chord practice

CHORD: "Practice a chord",

};

export type QuestionTypes = keyof typeof QUESTION_TYPES;The user’s lesson plan was stored in a global store that kept track of what was remaining, as well as completion progress for each lesson. Normally this would be stored in a database in a cloud on a per-user basis, but since my app is offline-friendly, it’s all stored locally. This means lesson plans aren’t huge (for now), and they’re often restricted to the user’s current level. This works great for the LLM integration, allowing us to generate lesson plans as we go - and cater them as needed.

Increasing accuracy

As I’ve mentioned, LLMs are susceptible to hallucination, particularly if the data falls outset it’s training set. To remedy this, we can provide the LLM with any information it needs. If the LLM isn’t sure what notes are in a certain chord, it can request that data from our app (which grabs it from a 3rd party music theory library). Or it can request additional context from our app, like the user’s learning history, to get a better context for the response.

We can achieve this by creating a “agentic” style flow, where the LLM “thinks” about a plan and can request additional data, then finally return a response. This is made possible by combining a few concepts: system prompts and OpenAI’s tool workflow.

Using system prompts we can instruct our LLM to expose it’s thinking to the user in a block of text we can parse, similar to our note extraction technique earlier.

The user will ask a question about music theory. Keep explanations short and concise.

If you want to display notes as sheet music, use the following format on a new line: <SheetMusic notes={["C4", "D4"]} pressed={[false, false]} />.

If they request notes, please share a copy of the notes at the end of the message in the format: '_NOTES_: [["C4", "D4", "E4"], ["A4", "C#3"]]'

For each step:

1. First, explain your thinking in a <thinking> tag

2. Then decide what action to take

3. After getting results, reflect on what you learned

Example:

<thinking>

To answer this question about the user's music experience, I need to:

- Query for user experience data

- Query for list of user's last 5 lessons

</thinking>This simply exposes the thinking to the user. It won’t actually do anything different until we provide some “tools” for it to use. This is easy using the OpenAI SDK, we just add a tools property to our new Completion alongside our messages.

const tools = [

{

type: "function",

function: {

name: "get_music_chord",

description: "Get musical chord using provided notes",

parameters: {

type: "object",

properties: {

notes: {

type: "array",

items: { type: "string" },

description: "Music notes",

},

},

required: ["notes"],

},

},

},

];Then we create a function that our tool can call.

const getMusicChord = (lessonDate: string[]) => {

// Get the chord

};

export const LLM_TOOLS = {

get_music_chord: getMusicChord,

};Then in the response we can check the response for the tools:

if (response.tool_calls && response.tool_calls.length > 0) {

response.tool_calls.forEach((tool) => {

console.log("calling tool", tool);

const toolData = JSON.parse(tool.function.arguments);

const toolFunction = LLM_TOOLS[tool.function.name];

const toolResult = toolFunction(toolData);

// Add tool result to working history

const toolResultMessage: ChatCompletionToolMessageParam = {

role: "tool",

tool_call_id: tool.id,

content: JSON.stringify(toolResult),

};

setChatLog((prev) => [...prev, toolResultMessage]);

chatLogCache.push(toolResultMessage);

});

} else {

console.log("no tools? loop over");

continueLoop = false;

// Ideally should stop loop when `finish_reason` is `stop`

}This allows us to reinforce the LLM with real data as it needs to curb the possibility of hallucinations. But keep in mind, this does increase the initial context with the tool definitions, so it comes at a cost.

With great power comes greater hallucinations

There’s a lot of space to explore the integration of LLMs. There’s a lot of potential, particularly in the backend and when paired with other data-driven systems. You can enable a lot of customization and control for the user that takes less time than custom tailoring that system from scratch. And the LLM works even better when combined with rigid and considered architecture, as it can form a safety net for the LLM and it’s many pitfalls.

With any new tech though, it’s important to look at it critically and remove it from any monument or pedestal. It’s got pros, and it’s got quite a few cons. LLM is not a silver bullet, and shouldn’t be the backbone of your innovation - or come with unnecessary cost (e.g. “why am I burning precious resources to do something a raspberry pi and a potato could do?”). But don’t let that stop you from having fun and learning along the way, it’s by opening our eyes to new potential that we can carve out a better future instead of rehashing the same boundaries each time.

The benefits I’ve found lean on the fundamental premise of the product: word association. It’s great for natural language parsing (perfect for searching or user prompts), linting language (like spotting grammatical or even code syntax issues), and language transformation (like changing from one code language to another). LLMs are built to follow their rules, and (depending on the model) most of the built-in rules include lots of standard stuff like classical music knowledge. This works great as a sounding post for topics, asking prompts like “hey what do you think of this thing?” and having the LLM provide a summarization of what scholars it’s scraped might have said. It’s not the same as speaking to an expert, but it’s a nice option when you don’t have one available - and particularly if you’re also an expert and are looking for alternate perspectives.

Would I use an LLM to learn music? Yeah it’s a great learning tool. Would it be my exclusive way of learning? Never. There’s no single source of truth that great. Would I recommend integrating an LLM to a music learning app? Absolutely, I think it has several use cases to enhance an ideally already well built app.

Stay curious, Ryo