I’ve got a quick one today for the motion design peeps. I’ve been experimenting with P5.js a bit lately to make 2D and 3D generative art, data visualizations, and animations. When it comes to animation in P5, things are really low level and manual. You have access to a few easy animation functions like lerp() — but it’s definitely not as actual easing functions - or even spring physics.

This got me thinking - what if I could use MotionJS (previously framer-motion) in P5 to handle the animation? It was surprisingly easy to setup, so I thought I’d share how it works.

Integrating P5 and Motion

Getting started with Motion

So how does Motion work? It takes a target - usually an element you want to animate like <button>, and then the “animation” itself.

import { animate } from "motion";

animate(".box", { opacity: 1 });

In this example from the Quick Start docs, we’re telling every HTML element with the box CSS class name to animate it’s opacity to 1.

All the other animation details are default, like the duration (I think it’s like 300ms?), or the animation type (linear, easing, spring, etc). Meaning any <div class="box"> or <button class="box"> would get their opacity animated.

But Motion also supports animating JavaScript objects — instead of HTML elements :

const animationState = {

opacity: 0,

};

animate(animationState, { opacity: 1 });

// If we used the object property, we can see it animate

console.log("Animation State", animationState);

<button style={{ opacity: animationState.opacity }} />;

In this example, we’re taking the animationState object and animating it’s opacity property. It works just like the method above with HTML elements.

Bringing it into P5

Now that we’ve got an understanding of Motion, let’s use it in P5.

You basically create an “animation state” object then use it whenever you want to animate. For this first example, we’ll make an animation that loops infinitely and moves an object from one position to another.

Here’s what the animation code would look like — no P5 involved:

let animationState = {

x: 0,

y: 0,

};

animate(

animationState,

{ x: 100, y: 100 },

{

duration: 0.5,

repeat: Infinity,

autoplay: true,

repeatType: "mirror",

}

);

We have an animationState object that has an x and y position (basically a “top” and “left” coordinate for our object we want to move around). Then we animate that object.

The key difference here from last time is that we pass an additional parameter to the animate() function. This parameter contains all the animation configuration details I mentioned earlier - like the duration. We can also tell Motion to repeat the animation a certain number of times - in this case we want to take advantage of the native JavaScript Infinity variable.

So where does this go in P5?

Since we’re looping infinitely, we probably want the animation to start right away. We can use P5’s setup() lifecycle function to start the animation once the canvas is loaded up.

let animationState = {

x: 0,

y: 0,

};

p.setup = () => {

console.log("setup canvas");

p.createCanvas(window.innerWidth, window.innerHeight);

p.frameRate(30);

animate(

animationState,

{ x: 100, y: 100 },

{

duration: 0.5,

repeat: Infinity,

autoplay: true,

repeatType: "mirror",

}

);

};

You’ll notice I use a

pprefix here for anyp5method. This is just part of my personal setup. If you wanted to use this on the P5 web editor for instance, you can just remove thep.prefix from everything and it’ll work the same.

Now we’ve got the animation started - let’s actually use it now. We need to use the animationState variable in the P5 draw() lifecycle function.

p.draw = () => {

console.log("animation", animationState);

// console.log('drawing!!')

p.background(p.color("#333")); // Set the background to off black

p.strokeWeight(10);

p.point(animationState.x, animationState.y);

};

And it’s that simple! You should have a dot on the screen that moves from 0, 0 to 100, 100 on your canvas.

You can a full example of this on CodePen or GitHub:

See the Pen P5.js + MotionJS Example by Ryosuke (@whoisryosuke) on CodePen.

More examples

Once you have the basics down, you can do some pretty interesting stuff with the Motion library. Here’s a few examples of experiments where I animated using Motion.

I won’t go too deep into these, but the full source code will linked for each one for reference (or if you want to take it for a spin).

Animating particles (aka piano keys)

This is a good example of what you’d want to use the animation library for. Spawning new objects and having those objects animate smoothly and independently.

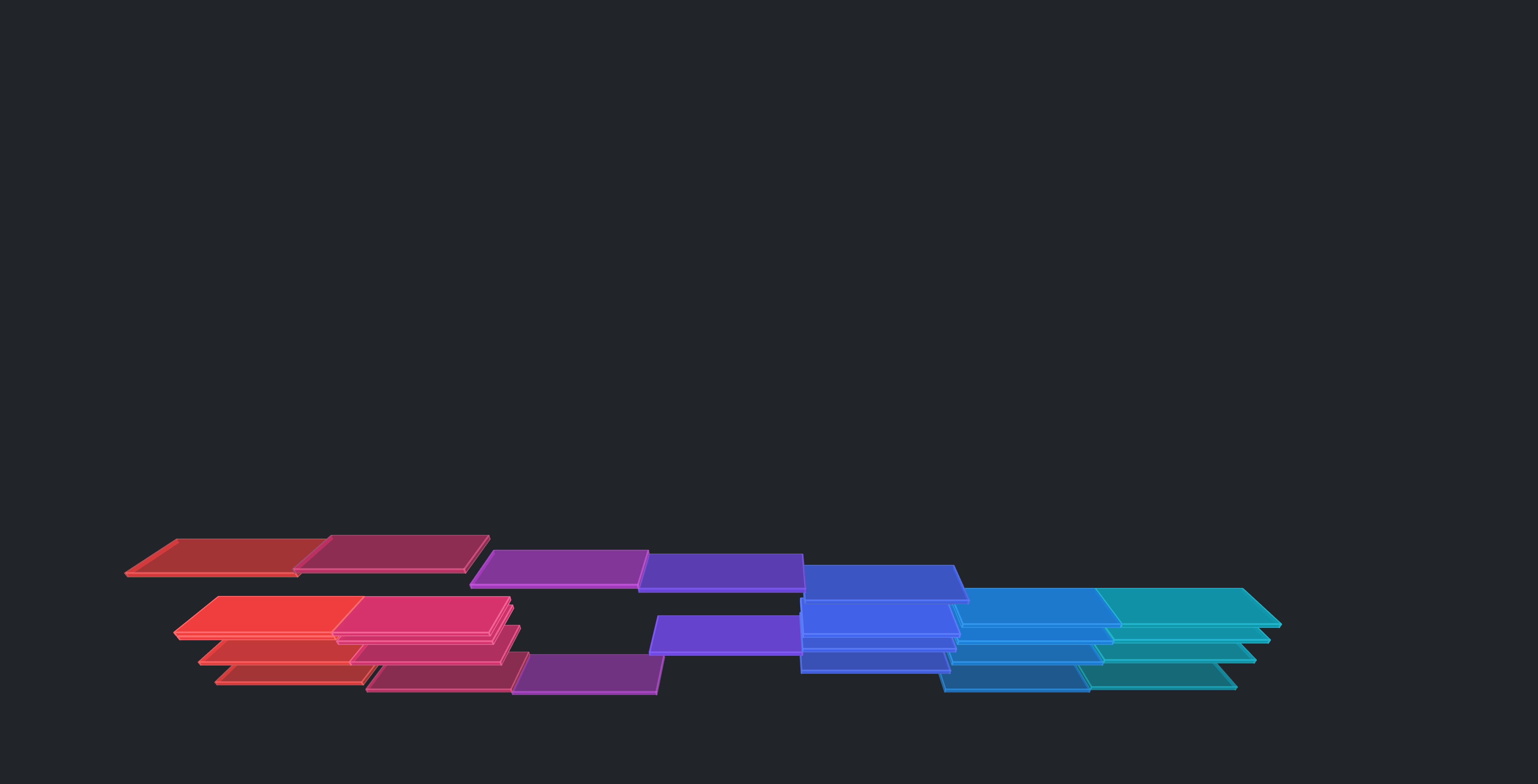

A still from the animation I created in P5 with colored squares spawning for piano key presses

A still from the animation I created in P5 with colored squares spawning for piano key presses

In this example I take MIDI keyboard playback (basically the input from a MIDI piano, drums, etc) and draw shapes on the screen that represent each piano key they press. The keys fade in and out using the Motion library.

This animation is based on the concept of “particles”, we let’s define what data those need and create a local array to add them to:

type NoteParticle = {

// A string representing a piano key (like C4, D4, etc)

note: Note;

// The timestamp when we created

created: number;

// Is particle marked for destruction?

destroy: boolean;

// The animation state

initialPosition: {

x: number;

y: number;

opacity: number;

};

};

const notes: NoteParticle[] = [];

The magic for this one happens in the draw() method. We basically need to check when a MIDI key is pressed. To do this, we have an app store that keeps track of the latest MIDI input data. Then we also have a local version of the MIDI input state that we check it against. This ensures that we only fire the function once per press - instead of constantly while it’s pressed.

p.draw = () => {

const { input } = useInputStore.getState();

// Check if notes changed

const inputState = Object.entries(input).filter(([noteKey, noteState]) =>

noteKey.includes("4")

);

inputState.forEach(([noteKey, notePressed]) => {

// Key was pressed or released

if (localInput[noteKey] !== notePressed) {

// Spawn a note if pressed

if (notePressed) {

// Create the particle here...

}

}

// Update our local state

localInput[noteKey] = notePressed;

}

}

To generate a piano key “particle", we create one based on the data type we defined earlier (NoteParticle) and add it to our local notes array. And when we push items to an array, it returns the new length of the array - so we save that to access the particle right after.

const newIndex = notes.push({

note: noteKey as Note,

created: time,

destroy: false,

initialPosition: {

x: keyX,

y: p.height - NOTE_HEIGHT,

opacity: 0,

},

});

Then we create the animation. Instead of targeting the animationState object, we use the particle object in our array (notes[newIndex - 1]). Motion is smart enough to keep track of the specific object in memory, so even if we add or remove from the array - it’ll keep animating that specific one.

const sequence: AnimationSequence = [

[

notes[newIndex - 1].initialPosition,

{

x: keyX,

y: p.height - NOTE_HEIGHT - 500,

opacity: 1,

},

{ duration: 1 },

],

[

notes[newIndex - 1].initialPosition,

{

x: keyX,

y: p.height - NOTE_HEIGHT - 1000,

opacity: 0,

},

{ duration: 1 },

],

];

animate(sequence);

}`

In this case I also use an animation sequence to give myself multiple “keyframes” to interpolate between. This lets us do a fade in and fade out animation to make things look as clean as possible.

Then we just draw all out particles like we need. I’d recommend creating a temporary copy of the particles to loop over, otherwise the notes may be out of date for that frame.

p.draw = () => {

const drawNotes = [...notes];

drawNotes.forEach((note) => {

// Draw them however you want

// Use `note.initialPosition` to animate something

}

}

You can see the full code here for reference on GitHub.

There’s a lot going on in this experiment behind the scenes to handle the MIDI input. If you’re interested in that kind of stuff, I’d check out my other blog articles on MIDI.

Controlled animations

I made a quick video renderer for P5.js that basically steps through an animation frame by frame and saves the canvas each time. I have a version that uses Motion to handle the animation.

Piano keys represented as colored blocks floating in 3D space

Piano keys represented as colored blocks floating in 3D space

The big difference here is that I keep the result of animate() as a variable called animationControls. This allows me to control the animation, like pausing or playing it. We also keep track of the current frameNumber we’re “rendering”.

let frameNumber = 0;

let animation = {

x: 0,

y: 0,

};

let animationControls: ReturnType<typeof animate>;

The method looks really similar, we setup an animation in P5’s setup() lifecycle. A small - but big difference here? We need to turn off autoplay. That way we can control the playback ourselves without it starting when we’re not ready.

p.setup = () => {

// Canvas setup omitted - but you get the idea

// We create an animation to control

animationControls = animate(

animation,

{ x: 100, y: 100 },

{

// This is important, make sure it's turned off

autoplay: false,

// Everything else is up to you!

// Duration of animation

duration: 0.5,

// Loops infinitely

repeat: Infinity,

// Makes it go back and forth (without creating a sequence yourself)

repeatType: "mirror",

}

);

Now here’s where the magic happens. In the P5 draw() lifecycle, we take advantage of the loop() and noLoop() functions. These functions do exactly what they say - they make P5 start or stop drawing.

We basically want P5 to only draw 1 frame at a time so we manually increment it ourselves. When we let P5 normally loop, it’s hard to control the time. More or less time could pass between frames if some get dropped by the user (like if the P5 graphic/animation gets too complex and the frame rate drops below what you originally set). We want to make sure we have every frame we need.

To make this happen, we’ll create a custom draw() function that we’ll call in the P5 setup lifecycle. This custom function will use loop() and noLoop() to start and stop the drawing (as well as actually draw stuff). Then we’ll have the function recursively call itself using a setTimeout() so we can set a time between frames to let the CPU/GPU chill out.

p.setup = () => {

// Canvas setup omitted - but you get the idea

const draw = () => {

// Lots of stuff we'll get into but basically...

p.loop()

p.point(animationState.x, animationState.y)

p.noLoop()

frameNumber += 1;

// Infinitely loops (with a delay)

setTimeout(draw, TIME_BETWEEN_FRAMES);

}

// Call the `draw()` method the first time so it can start looping infinitely

setTimeout(draw, TIME_BETWEEN_FRAMES);

}This setup lets us manually “loop” frame by frame to draw.

But how do we control Motion like this? With our animationControls from earlier! We can control the time property of the animation to change where it’s currently at in it’s “timeline”.

We use the frameNumber to determine what the current time is based off the frame rate of the animation we want (in my case, 60 FPS). Then pass that time to the animation controls.

const time = frameNumber / 60;

// We manually progress the animation by setting the time based on the frame counter

animationControls.time = time;

That simple! We do this every time we run the custom draw() function so we get the latest time. And if we use the animationState like we did before in our custom frame-by-frame loop, we’d get the right animation data.

const draw = () => {

// The time stuff I mentioned above...

// Now we draw

p.loop();

p.background(p.color("#333"));

p.strokeWeight(10);

p.point(animationState.x, animationState.y);

p.noLoop();

// setTimeout to loop again

};

In my video renderer experiment, I use an “offscreen texture” for rendering. This allows me to overlay UI on top of the rendered animation to let the user track render progress with an animated progress bar (and key details like the frame number or current time). Here’s the example on GitHub for reference on how that works. It also lets me export the video at the correct aspect ratio needed - in my case 4K.

And if you’re looking for a more complex example of this “video rendering” process using MotionJS, I also created an animated piano visualization using the same technique. You can find that piano visualizer code here on GitHub.

Putting the Motion back in graphics

Hope this blog helped enlighten you on the process for integrating MotionJS and p5.js, and the kind of cool stuff you can do with them together.

As always, if you make anything cool after learning from this - or have any questions - feel free to reach out on social media.

Stay curious, Ryo