I recently followed a wgpu tutorial that walks you through creating a WebGPU based 3D renderer using Rust. By the end, you’re rendering a 3D model (bananas in my case), along with a camera and light. The tutorial only has a parser for OBJ files, so I thought I’d figure out the process for parsing GLTF files. This would allow for a broader range of models to be imported, and even enable more features like animation!

Bananas rendered by WebGPU in Rust

In this article I’ll walk you through my process for expanding on the wgpu tutorial and adding GLTF support. We’ll parse GLTF files, load the 3D model into buffers (like all the texture/uniform data), and even build out a small animation system similar to production game engines like Unity or ThreeJS.

Final video of taking an animation from Blender to our Rust app

You can find the final source code here. Or you can clone this branch as a starting point.

📄 This is part of a series on wgpu in Rust. Find more posts in the #wgpu tag.

Learning about GLTF

The first thing I wanted to do was brush up on the GLTF spec and understand what I’d be parsing, and see what kind of data structure I had access to.

The next step was to make the simplest GLTF file I could think of to see the structure in action with minimal data to parse through. I opened up Blender, created a Plane object, and exported that as a GLTF file. This is where things already get interesting. During the export process you get the option to export a GLTF file, GLTF and Bin files (e.g. .gltf and .bin), or an embedded GLTF (aka .glb).

You might be asking yourself: why are there binary and embedded files? 3D models are so large in size, and the data that represents them isn’t really necessary for humans to parse themselves. Data like vertices, “normals”, or texture coordinates are all often loaded into a 3D engine using a buffer stream. Because of this, storing them in a binary format makes it quicker to load into a buffer stream (instead of loading raw JSON-like text, parsing that, then converting into a binary stream).

I didn’t want to go too far, since I didn’t plan on manually parsing the GLTF files myself, I planned on using a Rust crate that handles that. I was more interested in the structure of the data, because ideally, whatever parser I would use would probably just reflect the spec’s API back (in a Rust struct).

At this point I was pretty content with my digging. Although if you haven’t already, I’d learn about simpler formats like OBJ. The files are much easier to parse (yourself and by code). That’ll help understand basics like vertex or normal data (and how it should look or be structured).

The Audit

First I’d like to take a look at what we function we currently use to load models and how it works, that way we can borrow functionality and make sure it returns the right type.

Like I mentioned earlier, the wgpu tutorial sets up an OBJ parser to load 3D models. You can find it in the resources.rs file in this project.

pub async fn load_model(

file_name: &str,

device: &wgpu::Device,

queue: &wgpu::Queue,

layout: &wgpu::BindGroupLayout,

) -> anyhow::Result<model::Model> {

// Use our "clever" web or native loader

let obj_text = load_string(file_name).await?;

// Take the text and wrap it in a cursor (pre-cursor to the buffer if I may)

let obj_cursor = Cursor::new(obj_text);

// Put cursor in buffer

let mut obj_reader = BufReader::new(obj_cursor);

// Parse the text (in a buffer) using the tobj crate

let (models, obj_materials) = tobj::load_obj_buf_async(

&mut obj_reader,

&tobj::LoadOptions {

triangulate: true,

single_index: true,

..Default::default()

},

|p| async move {

let mat_text = load_string(&p).await.unwrap();

tobj::load_mtl_buf(&mut BufReader::new(Cursor::new(mat_text)))

},

)

.await?;

// Grab the data we need - like vertices and material info...

}

It’s a clever setup, since WebGPU runs on the web and native we need to load the data differently. On web we load using a URL that we generate from a static directory (that automatically gets uploaded to the server). On native we just load from the disk (aka person’s computer). This won’t change in our new setup.

What will change however, is the parsing logic (using the tobj crate), and the way we handle the data (since the structure aka Rust types will be different).

It also becomes clear that we need a new function for handling the model loading, because all the logic is all in one function. Luckily the web vs native loading logic is a separate function, so it makes the process easier.

Now we can move on to actually parsing a GLTF file.

The GLTF parser

One quick search online for Rust plus GLTF and the first thing that pops up is the gltf crate.

The documentation describes the process for installing (cargo install gltf) and how to get to the “nodes” in the scene (since GLTF files can multiple objects).

You can see in this commit I basically copy and paste the example from the docs into a new load_model_gltf() function, then try and dig a little deeper to find things like the meshes (or primitives) and materials.

use gltf::Gltf;

pub async fn load_model_gltf(

file_name: &str,

device: &wgpu::Device,

queue: &wgpu::Queue,

) -> anyhow::Result<bool> {

let gltf_text = load_string(file_name).await?;

let gltf_cursor = Cursor::new(gltf_text);

let gltf_reader = BufReader::new(gltf_cursor);

let gltf = Gltf::from_reader(gltf_reader)?;

for scene in gltf.scenes() {

for node in scene.nodes() {

println!("Node {}", node.index());

// dbg!(node);

let children = node.children().map(|child| {

dbg!(child);

});

let mesh = node.mesh().expect("Got mesh");

let primitives = mesh.primitives();

primitives.for_each(|primitive| {

// dbg!(primitive);

// Grab the material data (like texture)

let material = primitive.material().index();

// The index buffer data

let indices = primitive.indices();

// println!("{:#?}", &indices.expect("got indices").data_type());

// println!("{:#?}", &indices.expect("got indices").index());

// println!("{:#?}", &material);

});

}

}

Ok(true)

}

Running this code gets you some of the data, but it didn’t feel like I was getting everything I needed. I realized some of the properties, like the vertices, were hidden behind references to buffer streams (aka the .bin or .glb files with data).

I started to take a step back here and go back into research mode.

The Bevy Lifeline

As I looked closer at the documentation, I had a hard time figuring out how to get the data I needed. There weren’t clear examples, and the disambiguated structs were hard to navigate (even with my IDE tooltip context).

I remembered that Bevy uses wgpu under the hood, so I checked and luckily, they had a way to import GLTF files using the same crate. At this point I started to heavily reference the Bevy codebase to understand how to navigate through the various structs and enums.

Parsing GLTF buffers

Now we’re cooking, thanks to Bevy’s code, I was able to understand how the buffers() property works.

pub async fn load_model_gltf(

file_name: &str,

device: &wgpu::Device,

queue: &wgpu::Queue,

) -> anyhow::Result<bool> {

let gltf_text = load_string(file_name).await?;

let gltf_cursor = Cursor::new(gltf_text);

let gltf_reader = BufReader::new(gltf_cursor);

let gltf = Gltf::from_reader(gltf_reader)?;

// Load buffers

let mut buffer_data = Vec::new();

for buffer in gltf.buffers() {

match buffer.source() {

gltf::buffer::Source::Bin => {

// if let Some(blob) = gltf.blob.as_deref() {

// buffer_data.push(blob.into());

// println!("Found a bin, saving");

// };

}

gltf::buffer::Source::Uri(uri) => {

let bin = load_binary(uri).await?;

buffer_data.push(bin);

}

}

}

for scene in gltf.scenes() {

for node in scene.nodes() {

let mesh = node.mesh().expect("Got mesh");

let primitives = mesh.primitives();

primitives.for_each(|primitive| {

let reader = primitive.reader(|buffer| Some(&buffer_data[buffer.index()]));

if let Some(vertex_attibute) = reader.read_positions().map(|v| {

dbg!(v);

}) {

// Save the position here using mapped vertex_attribute result

}

});

}

}

Ok(true)

}

You call gltf.buffers() to get an array of buffers that you can loop over and call the buffer.source() method to get the underlying data. This is an enum gltf::buffer::Source that represents either a Bin or Uri. Now this is confusing, because you’d think that Bin means it’s the .bin file — but it’s actually when the binary data is embedded inside the same file. The Uri actually holds our .bin info.

Once we have the buffer, we store it in a Vec to access later.

Then while we loop over our scene and each node, we can use the reader() method on each Primitive to get the index of the buffer we want, then we can use that same index to grab the buffer from the Vec we created earlier.

This new reader variable gives us access to a lot of different data points. In this example, I grab the position data, but later we’ll also use this same variable to access the normals and texture coordinates.

Grabbing the rest

Now that we have access to the mesh data we can store it inside our app. The way we represent 3D mesh data in the app is using the Model struct (from the wgpu tutorial). That Model struct contains a ModelVertex struct that contains our mesh’s position, normal, and texture data for each vertex. This is the same struct we use to load data into the buffers of the render pipeline (like the vertex or index buffer).

We create a mutable vertices variable at the top that we’ll fill with ModelVertex structs. Then when we loop over each mesh data property (like position), we “push” the data into the vertices.

let mut vertices = Vec::new();

if let Some(vertex_attribute) = reader.read_positions() {

vertex_attribute.for_each(|vertex| {

dbg!(vertex);

vertices.push(ModelVertex {

position: vertex,

tex_coords: Default::default(),

normal: Default::default(),

})

});

}

if let Some(normal_attribute) = reader.read_normals() {

let mut normal_index = 0;

normal_attribute.for_each(|normal| {

dbg!(normal);

vertices[normal_index].normal = normal;

normal_index += 1;

});

}

if let Some(tex_coord_attribute) = reader.read_tex_coords(0).map(|v| v.into_f32()) {

let mut tex_coord_index = 0;

tex_coord_attribute.for_each(|tex_coord| {

dbg!(tex_coord);

vertices[tex_coord_index].tex_coords = tex_coord;

tex_coord_index += 1;

});

}

let mut indices = Vec::new();

if let Some(indices_raw) = reader.read_indices() {

// dbg!(indices_raw);

indices.append(&mut indices_raw.into_u32().collect::<Vec<u32>>());

}

dbg!(indices);

You’ll also see that for indices we just store it in a separate Vec of u32 — that’s because that buffer is separate and essentially an array of integers.

Here’s the commit so far for context.

Now we can create the buffers and return the Model to use in the app.

let vertex_buffer = device.create_buffer_init(&wgpu::util::BufferInitDescriptor {

label: Some(&format!("{:?} Vertex Buffer", file_name)),

contents: bytemuck::cast_slice(&vertices),

usage: wgpu::BufferUsages::VERTEX,

});

let index_buffer = device.create_buffer_init(&wgpu::util::BufferInitDescriptor {

label: Some(&format!("{:?} Index Buffer", file_name)),

contents: bytemuck::cast_slice(&indices),

usage: wgpu::BufferUsages::INDEX,

});

meshes.push(model::Mesh {

name: file_name.to_string(),

vertex_buffer,

index_buffer,

num_elements: indices.len() as u32,

// material: m.mesh.material_id.unwrap_or(0),

material: 0,

});

Here’s this commit for context.

Texture time

Almost there. You might be able to run the code so far, but you’d encounter an error from the shader asking for texture data. If you removed the texture from the shaders, you should be able to see the mesh though. But we want texture support, so lets do that!

What we’re interested in is the mesh’s “material”, which will contain any texture data (like images), as well as other properties. GLTF supports the PBR (or physically based rendering) rendering model, which lets you get properties from the mesh like roughness to make things look metallic or reflective.

This was another area I needed to reference the Bevy codebase, because the GLTF crate docs didn;t make it too clear how to access everything (I mean, just look at that .source().source() down there — what’s going on).

let mut materials = Vec::new();

for material in gltf.materials() {

println!("Looping thru materials");

let pbr = material.pbr_metallic_roughness();

let base_color_texture = &pbr.base_color_texture();

let texture_source = &pbr

.base_color_texture()

.map(|tex| {

println!("Grabbing diffuse tex");

dbg!(&tex.texture().source());

tex.texture().source().source()

})

.expect("texture");

match texture_source {

gltf::image::Source::View { view, mime_type } => {

let diffuse_texture = texture::Texture::from_bytes(

device,

queue,

&buffer_data[view.buffer().index()],

file_name,

)

.expect("Couldn't load diffuse");

materials.push(model::Material {

name: material.name().unwrap_or("Default Material").to_string(),

diffuse_texture,

});

}

gltf::image::Source::Uri { uri, mime_type } => {

let diffuse_texture = load_texture(uri, device, queue).await?;

materials.push(model::Material {

name: material.name().unwrap_or("Default Material").to_string(),

diffuse_texture,

});

}

};

}

The top level of the GLTF struct has a materials property that you can loop over. With each material, you can call a pbr_metallic_roughness() method to get the PBR properties. These properties also contain the texture data (which could be multiple images, like diffuse and roughness textures). We can use the base_color_texture() method to get the diffuse texture from the mesh (aka the general color - an image you’d see projected onto the mesh).

Once we get the texture we need, we still need to figure out how to load it. Just like our vertex data previously, our texture data can be stored either in the .bin file — or a separate image file (.jpg, .png, etc). The texture we get from our mesh is a gltf::image::Source enum, so we match that to get either a View (aka inside the .bin) or Uri (aka separate image file).

For the View type, we need to handle it the same we got our vertex buffer data. We grab it from the buffer data using the index provided by the View (view.buffer().index()). Since the data we get back is a binary stream, we can use our existing from_bytes() method to convert the bytes to an actual image our render pipeline understands.

The Uri option is way simpler, and you can just use the load_texture() method that takes the URL and loads it into a binary stream (depending on web vs native).

With both results, we get a diffuse texture that we can push inside our Vec of materials. This should give us texture support! If you try the renderer here with a textured GLTF model, it should work.

Check out this commit for reference (comes with a textured GLTF model of my avatar).

Animation Research

Loading models and their materials are great, but what would be even cooler? Loading animations! One of the great strengths of the GLTF format is that it can store multiple animations. You can see an example here using React Three Fiber and ThreeJS where one GLTF model is loaded and multiple animations can be played from the same file.

How does this work? When you make models in apps like Blender, you get the option to create “animation clips”. These are entire animation sequences that can move, rotate, scale, and modify the mesh in other ways. By creating multiple clips, it lets the 3D artist do things like make a walk cycle, then a jump animation, all in the same file.

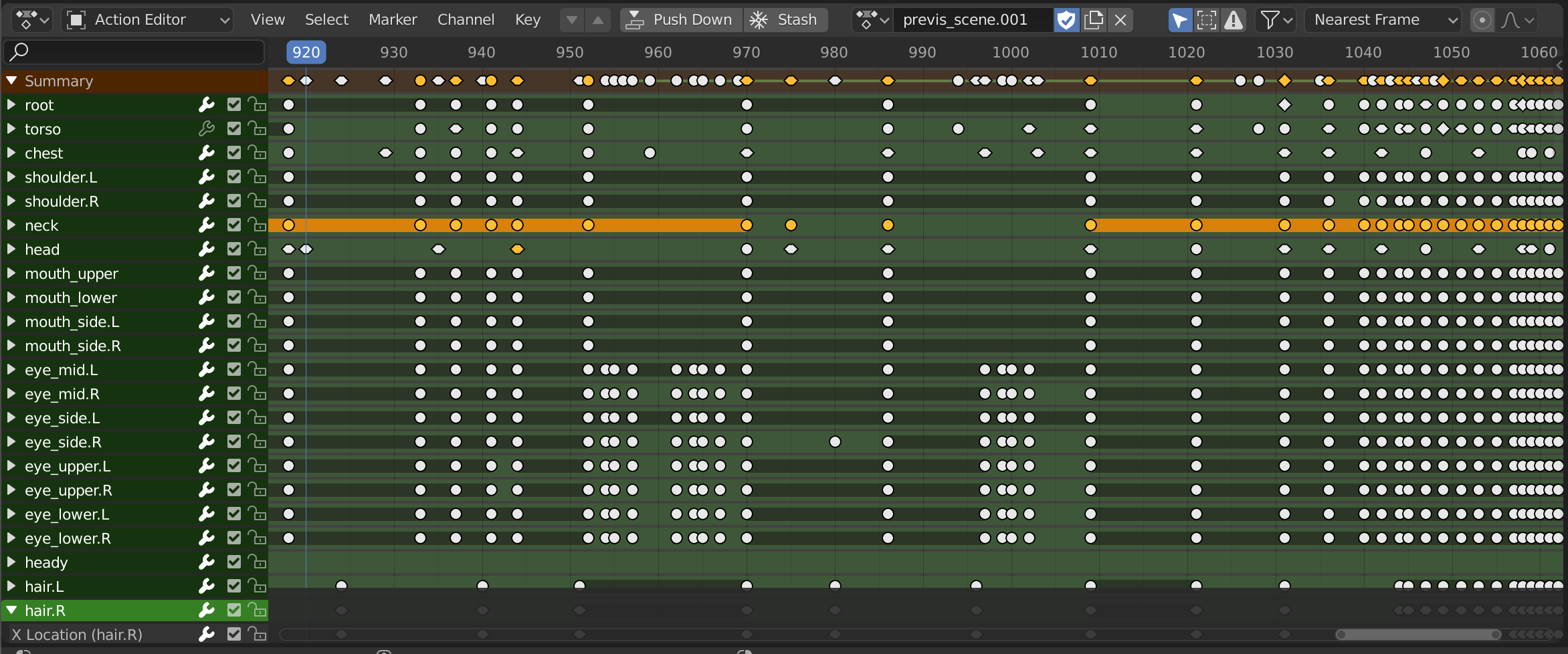

Screenshot of the Blender Action Editor window with several elements of model animated (in this case, a skeletal rig). From the Blender docs.

Screenshot of the Blender Action Editor window with several elements of model animated (in this case, a skeletal rig). From the Blender docs.

You can save your 3D model with these animation clips in file format that supports animations (.gltf, .fbx, etc). Then you can import it into apps like Unity or Unreal Engine, which parse the file into their own engine’s version of “animation clips”. You can find this concept of “Animation Clips” in other libraries as well, like ThreeJS or Bevy.

For example, here’s Unity’s AnimationClip class. When you import a 3D file with animations, each one becomes a AnimationClip, or you could create them from scratch using Unity’s animation editor.

A screenshot of the Unity asset library window showing a 3D model, each mesh and material inside it, and animation clips defining different movements. In this case, it’s a 3D model of a gamepad, and each animation is a different button press.

A screenshot of the Unity asset library window showing a 3D model, each mesh and material inside it, and animation clips defining different movements. In this case, it’s a 3D model of a gamepad, and each animation is a different button press.

When you take a look at these data structures for “animation clips”, you’ll find they look very similar to the Blender Action Editor we saw above. There are several “tracks” (in case we have multiple meshes inside our model - or a skeletal rig), each with their own set of “keyframes” that represent the animation time, and whatever modifications occur to mesh (like translation aka moving it).

Parsing Animations

Now that we have an idea of how this concept is generally handled across several 3D apps and engines, let’s see what it takes to implement it inside our own engine.

It’s clear we’re going to need new structs to store our animation data. But before we do that, let’s just figure out how to get the data out (using possibly a peek at the Bevy source).

// Load animations

for animation in gltf.animations() {

for channel in animation.channels() {

let reader = channel.reader(|buffer| Some(&buffer_data[buffer.index()]));

let keyframe_timestamps = if let Some(inputs) = reader.read_inputs() {

match inputs {

gltf::accessor::Iter::Standard(times) => {

let times: Vec<f32> = times.collect();

println!("Time: {}", times.len());

// dbg!(times);

}

gltf::accessor::Iter::Sparse(_) => {

println!("Sparse keyframes not supported");

}

}

};

let mut keyframes_vec: Vec<Vec<f32>> = Vec::new();

let keyframes = if let Some(outputs) = reader.read_outputs() {

match outputs {

gltf::animation::util::ReadOutputs::Translations(translation) => {

translation.for_each(|tr| {

// println!("Translation:");

// dbg!(tr);

let vector: Vec<f32> = tr.into();

keyframes_vec.push(vector);

});

},

other => ()

// gltf::animation::util::ReadOutputs::Rotations(_) => todo!(),

// gltf::animation::util::ReadOutputs::Scales(_) => todo!(),

// gltf::animation::util::ReadOutputs::MorphTargetWeights(_) => todo!(),

}

};

println!("Keyframes: {}", keyframes_vec.len());

}

}

This process was very similar to getting access to the vertex buffer. We loop over all the animations (or “animation clips” aka “jump” or “walk cycle”). Then we loop over each “channel” in the animation (or “track”) and use the reader() method to get the buffer index and create a Reader for the data. Finally we can use the read_inputs() and read_outputs() methods to get the two data points we want — time and animation data (like translation, or rotation).

What does the data look like? When we eventually parse, we get something that looks like this:

× = [

0.041666668,

0.083333336,

0.125,

0.16666667,

0.20833333,

0.25,

// Continues incrementing to the max below

2.5,

]

// The "translations" aka new position of mesh

[src\resources.rs:215] &tr = [

0.0,

0.0,

-0.0,

]

[src\resources.rs:215] &tr = [

0.0,

0.0069703558,

-0.0,

]

[src\resources.rs:215] &tr = [

0.0,

0.027225388,

-0.0,

]

The time is returned in an array, from 0 seconds to the end time of animation (2.5s in this case). Then for each “translation”, it’s returned as an 3D vector (aka XYZ coordinates in an array). For every time we have in the first array, we should have a corresponding translation (aka times.len() == translations.len()).

You can find this commit here for reference.

Animation Structure

Now that we have our animation data, let’s create a data structure that supports it.

We know we have “animation clips” that represent different actions (like jump or walk cycle). We also timestamps (defining the animation points in time), and the keyframes with our animation data. Now I mentioned before we’re doing “translation” animation (moving mesh). But there might be other types of animation supported in the future (like rotating or scale). So to allow for this, we create an enum for keyframes, and store the value inside that (for translation, it’s a XYZ coordinate, so a vector of vectors with floats (aka [ [ 0.0,0.0,0.0 ], [ 0.0,1.0,0.0 ] ]). In the future, we might need a Rotation type that supports quaternions or something.

pub enum Keyframes {

Translation(Vec<Vec<f32>>),

Other,

}

pub struct AnimationClip {

pub name: String,

pub keyframes: Keyframes,

pub timestamps: Vec<f32>,

}

pub struct Model {

pub meshes: Vec<Mesh>,

pub materials: Vec<Material>,

pub animations: Vec<AnimationClip>,

}

These structs can go inside our Model module, since we already have our Material in there, which is also closely associated to the Model.

Now that we have data structures, let’s go back to our animation parsing and use them.

// Load animations

let mut animation_clips = Vec::new();

for animation in gltf.animations() {

for channel in animation.channels() {

let reader = channel.reader(|buffer| Some(&buffer_data[buffer.index()]));

let timestamps = if let Some(inputs) = reader.read_inputs() {

match inputs {

gltf::accessor::Iter::Standard(times) => {

let times: Vec<f32> = times.collect();

println!("Time: {}", times.len());

// dbg!(times);

times

}

gltf::accessor::Iter::Sparse(_) => {

println!("Sparse keyframes not supported");

let times: Vec<f32> = Vec::new();

times

}

}

} else {

println!("We got problems");

let times: Vec<f32> = Vec::new();

times

};

let keyframes = if let Some(outputs) = reader.read_outputs() {

match outputs {

gltf::animation::util::ReadOutputs::Translations(translation) => {

let translation_vec = translation.map(|tr| {

// println!("Translation:");

// dbg!(tr);

let vector: Vec<f32> = tr.into();

vector

}).collect();

Keyframes::Translation(translation_vec)

},

other => {

Keyframes::Other

}

// gltf::animation::util::ReadOutputs::Rotations(_) => todo!(),

// gltf::animation::util::ReadOutputs::Scales(_) => todo!(),

// gltf::animation::util::ReadOutputs::MorphTargetWeights(_) => todo!(),

}

} else {

println!("We got problems");

Keyframes::Other

};

animation_clips.push(AnimationClip {

name: animation.name().unwrap_or("Default").to_string(),

keyframes,

timestamps,

})

}

}

With this Vec of AnimationClip now, we can pass it to the Model we return from this method and we should have all the animation data we need.

You can find this here commit for reference.

Playing Animations

But how do we play this animation in our 3D WebGPU engine? We’ll need a few things: first, a concept of time, and second, a system for playing animations.

To our app state, we’ll add a new property for time and use the Instant struct that the Rust standard library provides. This will be a quick and simple way to define a timer that runs when we start our app.

use std::{iter, time::Instant};

struct State {

// Animation

time: Instant,

}

Then during our app’s initialization process, we can setup our time variable:

let time = Instant::now();

Cool, now that we have the concept of time in our app, we can use it to “play” the animations. In our app’s update() lifecycle, we can loop through all of our models and play the first animation we find (ideally later we can play by animation clip name - like “jump” vs “walk”).

println!("Time elapsed: {:?}", &self.time.elapsed());

// Update local uniforms

let current_time = &self.time.elapsed().as_secs_f32();

let mut node_index = 0;

for node in &mut self.nodes {

// Play animations

if node.model.animations.len() > 0 {

// Loop through all animations

// TODO: Ideally we'd play a certain animation by name - we assume first one for now

let mut current_keyframe_index = 0;

for animation in &node.model.animations {

for timestamp in &animation.timestamps {

if timestamp > current_time {

break;

}

if ¤t_keyframe_index < &(&animation.timestamps.len() - 1) {

current_keyframe_index += 1;

}

}

}

// Update locals with current animation

let current_animation = &node.model.animations[0].keyframes;

let mut current_frame: Option<&Vec<f32>> = None;

match current_animation {

Keyframes::Translation(frames) => {

current_frame = Some(&frames[current_keyframe_index])

}

Keyframes::Other => (),

}

if current_frame.is_some() {

let current_frame = current_frame.unwrap();

node.locals.position = [

current_frame[0],

current_frame[1],

current_frame[2],

node.locals.position[3],

];

}

}

// node.locals.position = [

// node.locals.position[0],

// (node.locals.position[1] + 0.001),

// (node.locals.position[2] - 0.001),

// node.locals.position[3],

// ];

&self

.pass

.uniform_pool

.update_uniform(node_index, node.locals, &self.ctx.queue);

node_index += 1;

}

}

We “play” the animation by taking the “translation” animation data and applying it to our model’s local uniforms. These already contain things like the object’s position, so we can just update this to our animation position. This “local” data gets transferred to the shader, which updates the mesh appropriately.

You can the commit here for reference.

📄 If you followed the wgpu tutorial and you got here and wondering what are “local uniforms” and what is this magic

update_uniformmethod? That’s ok! This functionality is something I added when implementing an ECS-like system for rendering multiple objects (something the original tutorial didn’t include). If you start from my repo and the branch I recommend above, you should have access to this.

This should play when we start our app! You can see a video of the app in action here.

Final thoughts

The gltf crate docs could definitely use some more solid and practical examples, particularly for the specific “Reader” pattern they’re using. It’d be cool if there were even some helper methods that encapsulated some of the logic for simpler situations where I didn’t need as much flexibility or control.

One of the things that made this process much easier was how fantastic the Rust type system and IDE experience is. Whenever I would hit a wall where I didn’t know what a certain data type was, it was always just 1 hover tooltip away. And for things like enum, the ability to fill out all the match cases is a time and brain bandwidth saver.

Hope this helps you get started adding GLTF support to your Rust apps, and understanding the GLTF spec and it’s potential a bit more. As always, if you have any questions or want to share your project, feel free to message me on Twitter or Mastodon.